The latest exhibition, Once Upon a Tide at the National Museum of Singapore is nothing short of spectacular. I was very impressed by the design and the overall visitor experience. In short, “a blockbuster-tier production”.

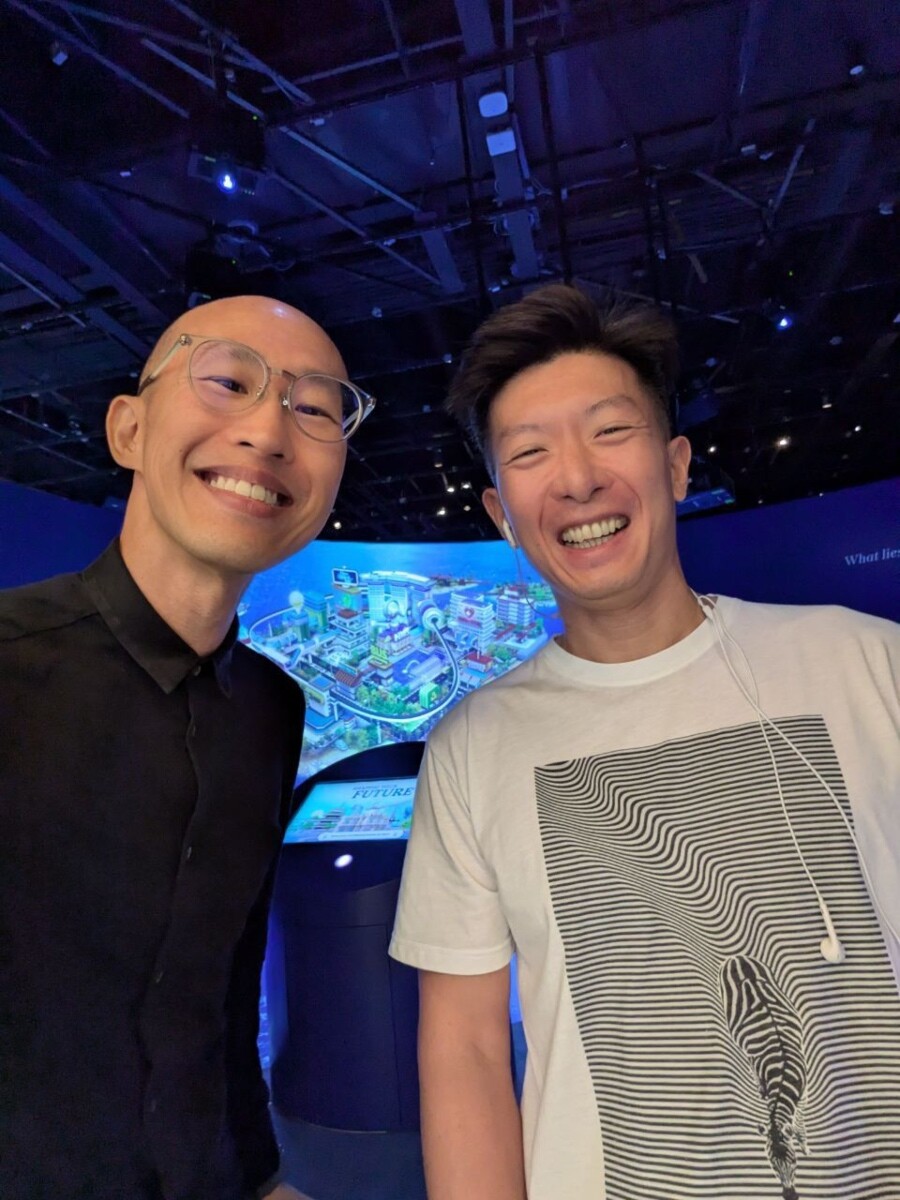

The process of creating this exhibition involves many stages. It includes research, curatorial development, artifact acquisition or preparation, design, fabrication, and installation. Mr Daniel Tham, the lead curator of this exhibition, together with his team gave a media preview this week and I was fortunate to be one of the attendees.

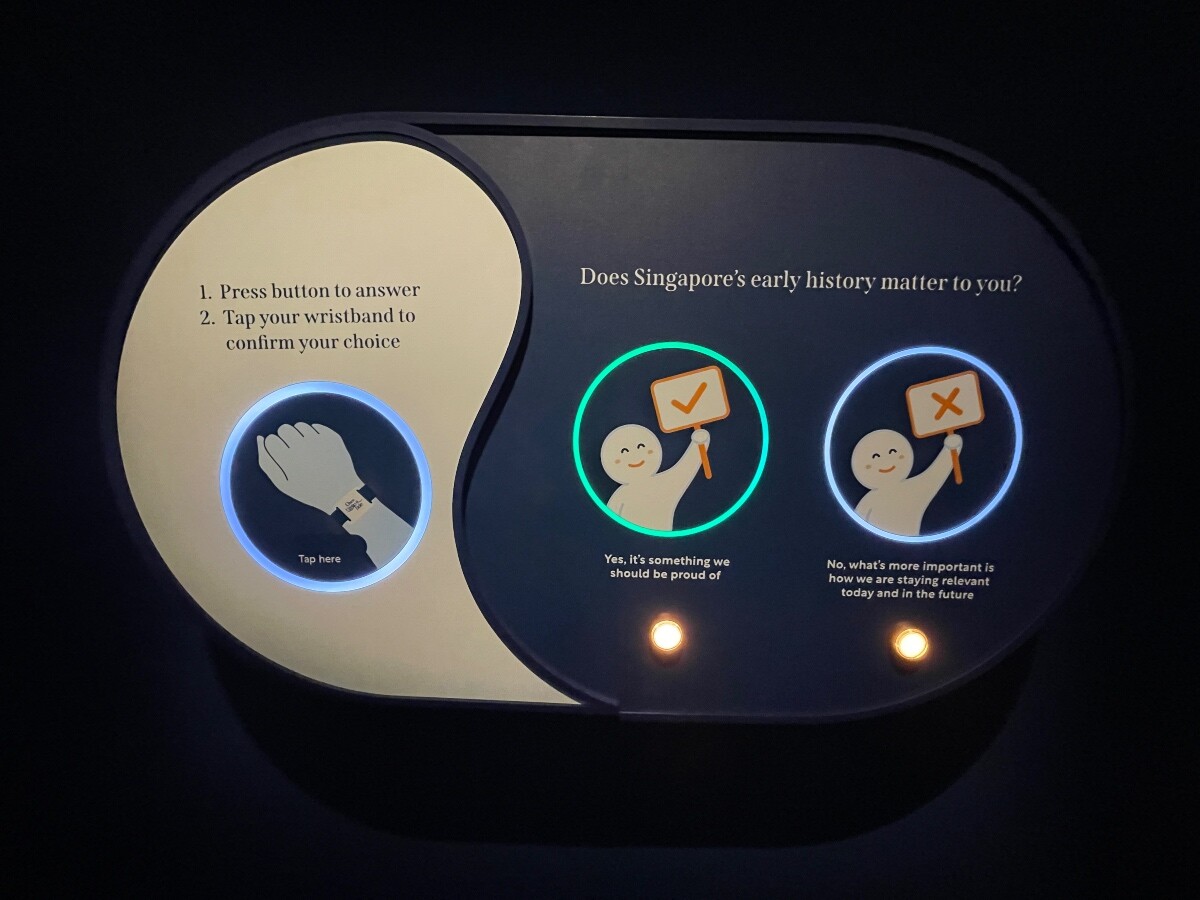

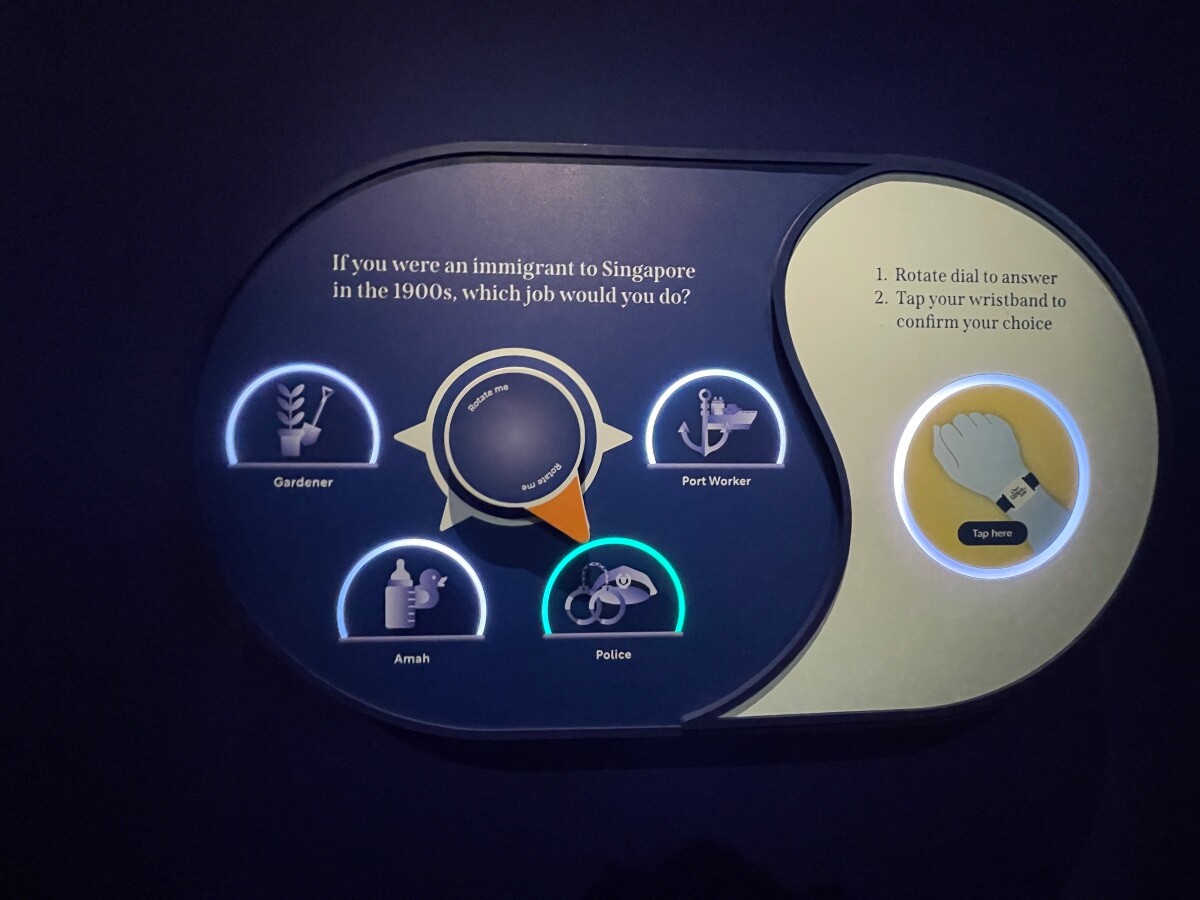

Before we begin, we each have a wrist tag that we will use during our interactive tour.

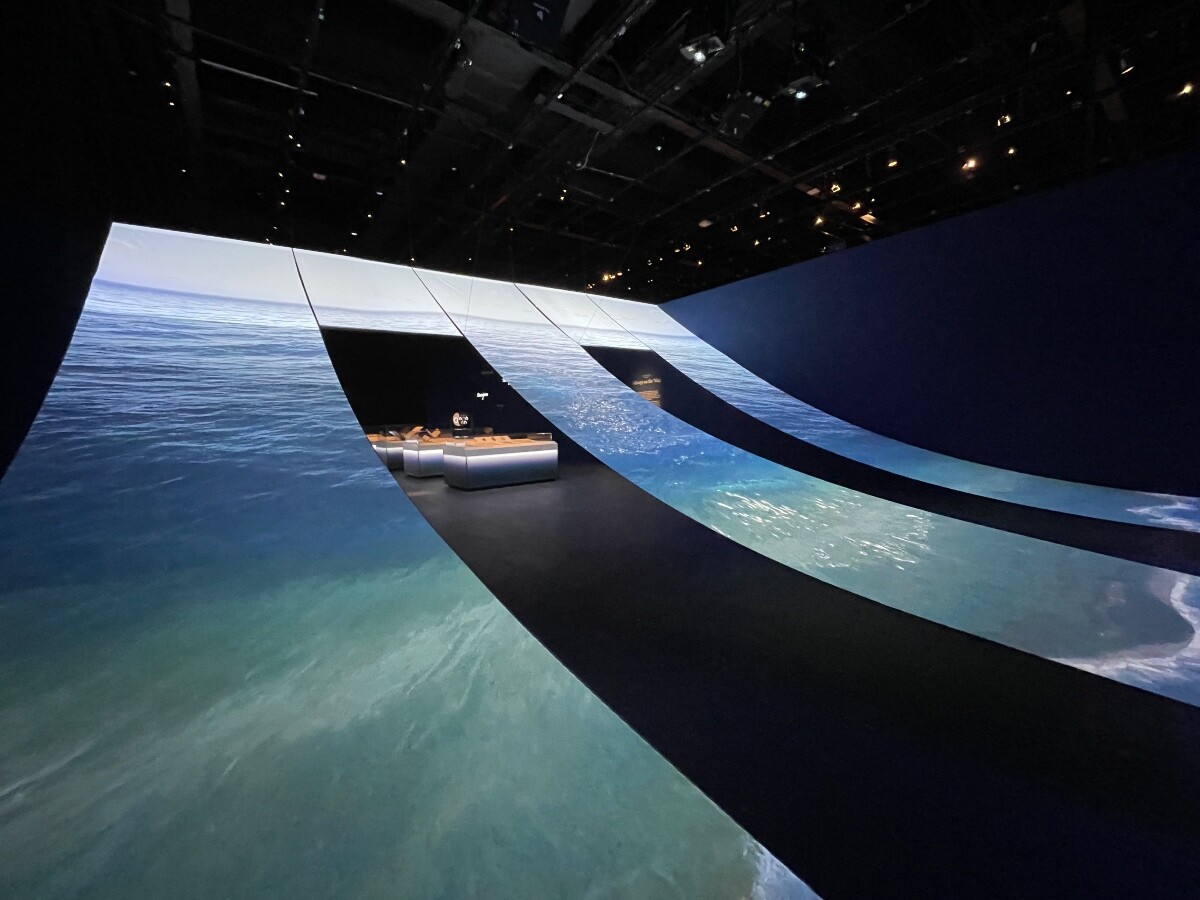

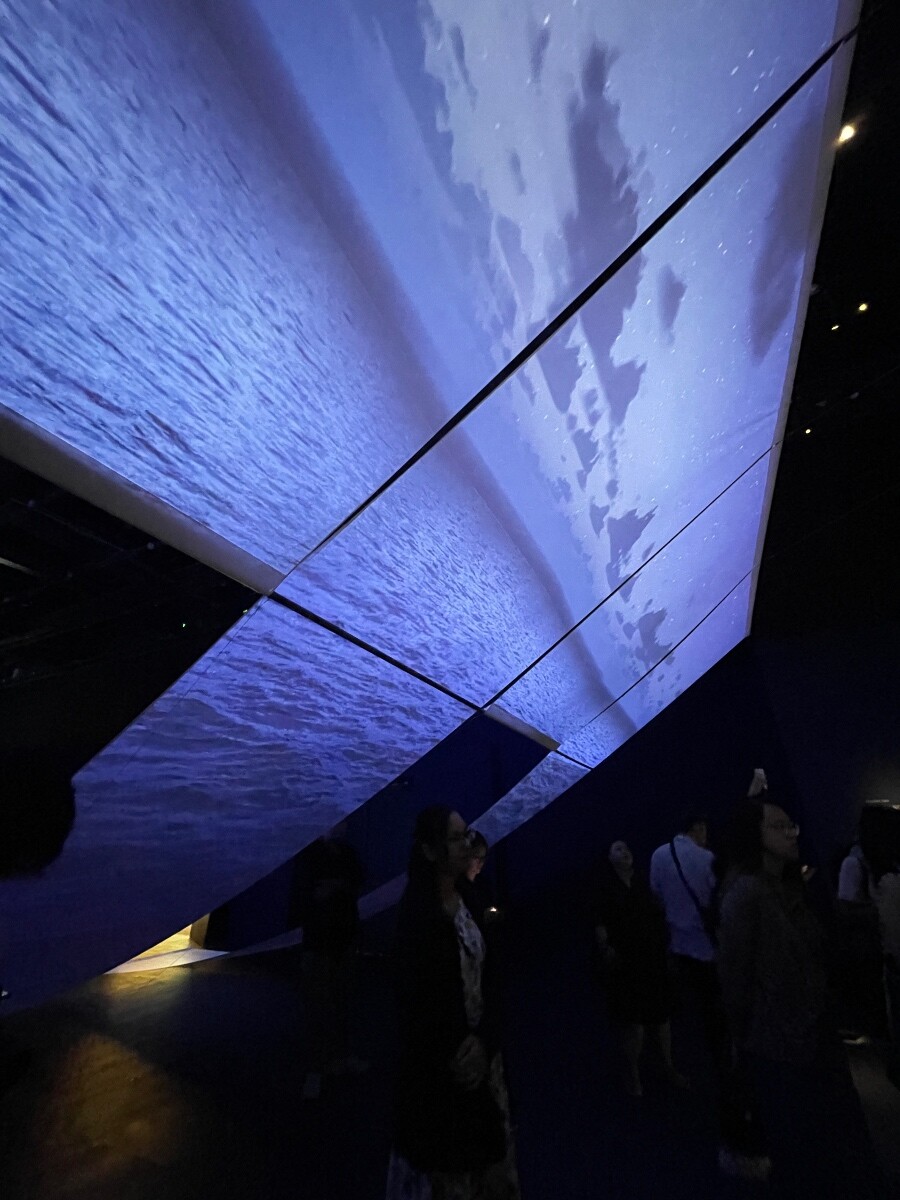

The first exhibit upon entering is well-thought and all out visually captivating. It was assembled by a series of long panel screens that display the sea waves projections from the projectors above at precise angles. The story of Singapore begins nowhere but from the exploration of seas. Explorers who ventured beyond their territories and by chance or fate, discovered our tiny plain island.

Here, as you enter the exhibition hall “from the sea”, you leave the ocean body behind you. You step into Singapore, or Temasek, as it was known before it was renamed Singapura. Temasek means “Sea Town” in Old Javanese and this was the name used primarily during the 14th century.

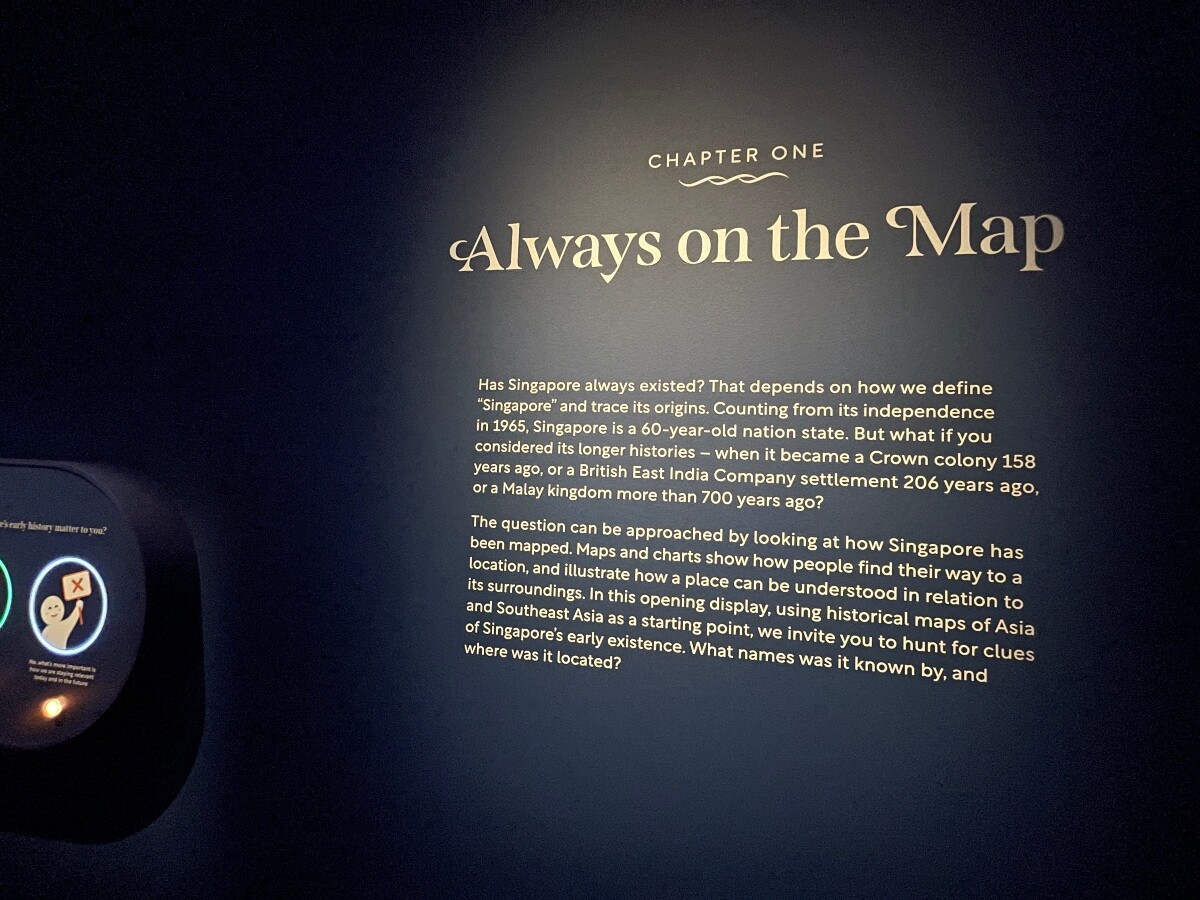

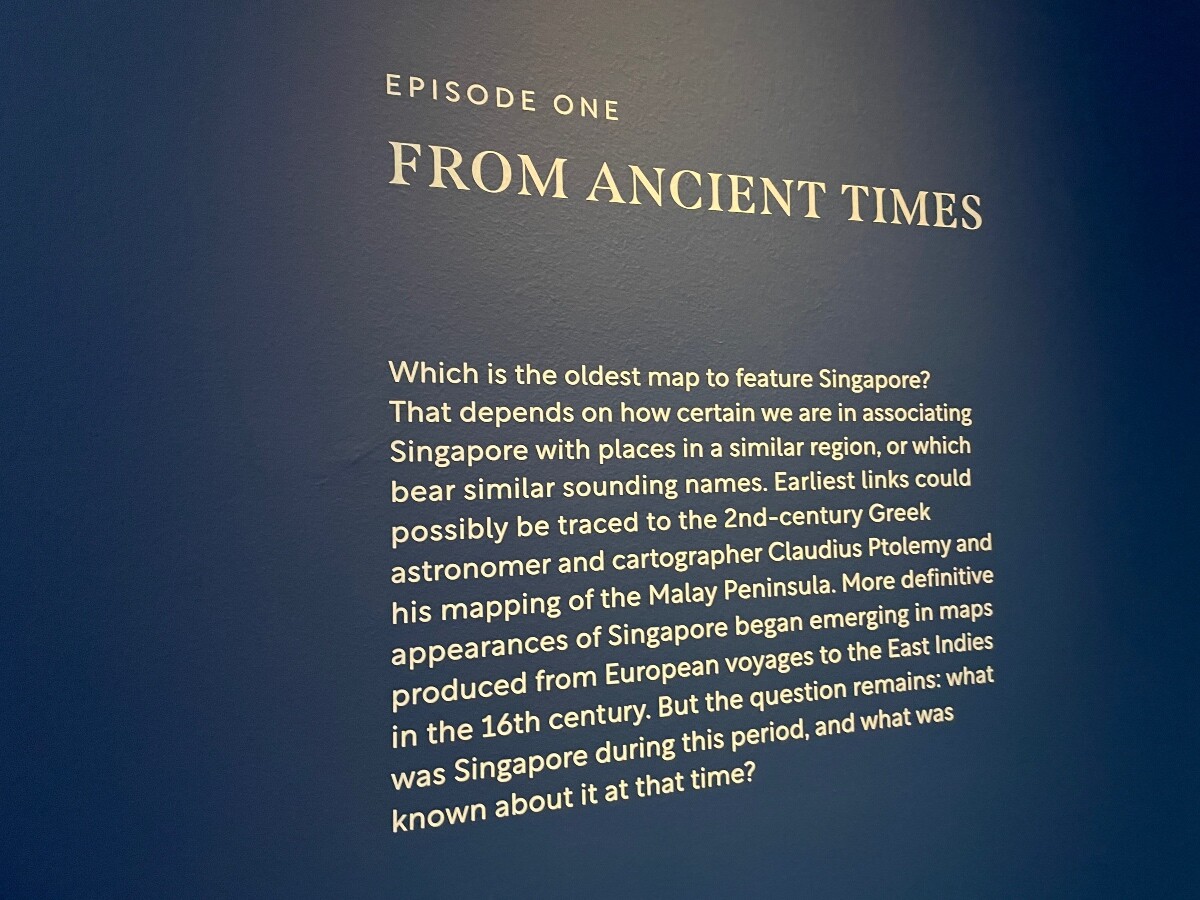

Chapter One: Always on the Map

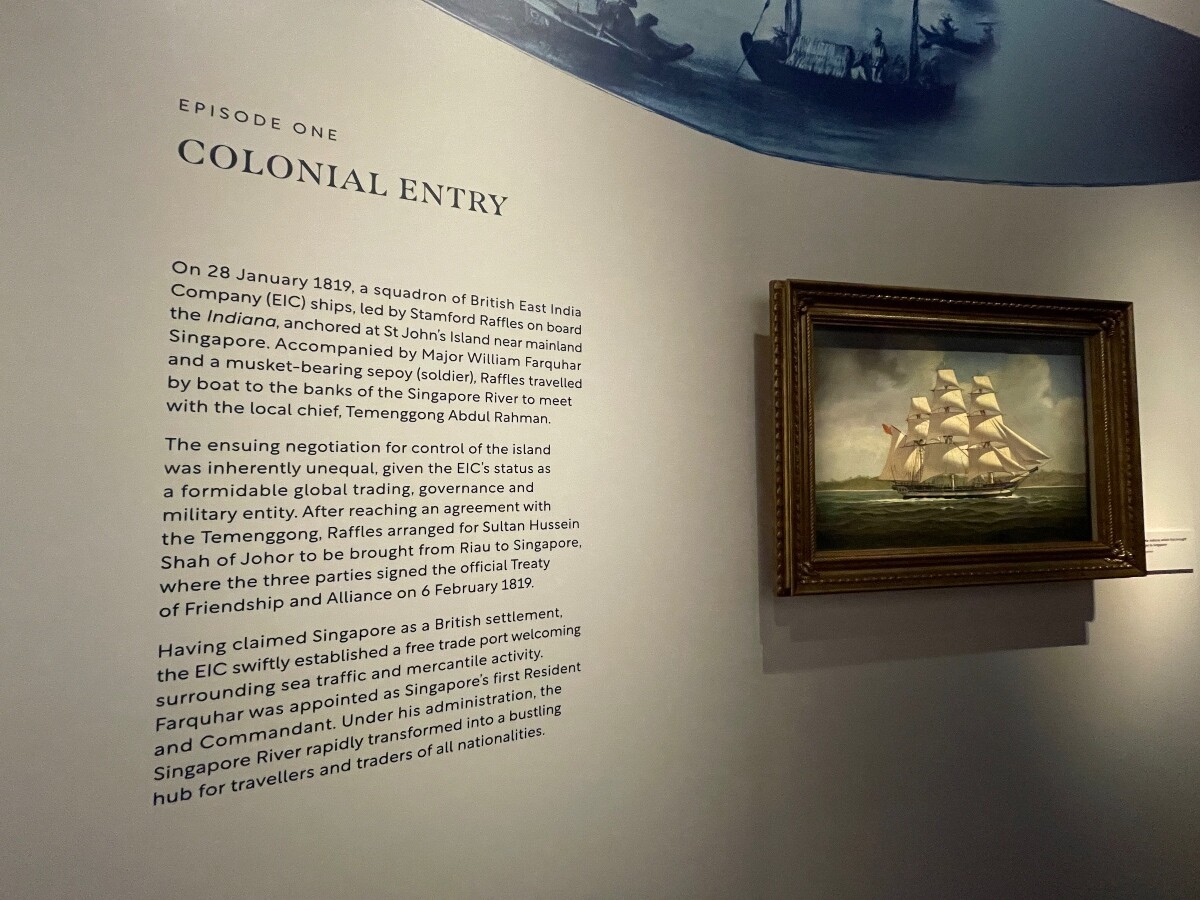

The exhibition unfolds as an immersive saga, thoughtfully divided into five captivating chapters. Your journey begins in Chapter One, designed to evoke a sense of anticipation. The hall’s dim, dusky twilight deliberately mirrors the pre-dawn uncertainty faced by early adventurers. Strategic spotlights illuminate key treasures, each beam cutting through the gloom.

Published in 1732 by Ibrahim Muteferrika, this hand-colored engraving of Sumatra offers a glimpse into historical geographical ambiguity. The map, from the 17th-century Ottoman scholar Katib Celebi’s “Kitab Cihannuma,” highlights the prevailing uncertainty regarding Singapore’s precise location then. “Singapur” (in Arabic) is imprecisely identified on the map as the entire southern Malay Peninsula, south of the Muar River.

Major P. D. R. Williams-Hunt found stone adzes on Pulau Ubin’s western side, near Tanjong Tajam beach. These adzes, possibly basalt, potentially date 3,000 – 5,000 years (Hoabinhian-Neolithic); early people likely fashioned them. Williams-Hunt collected these prehistoric tools in the late 1940s/early 1950s, and they offer insights into early Singapore. At the time, he was Malaya’s Acting-Director of Museums and an active field researcher in Southeast Asia.

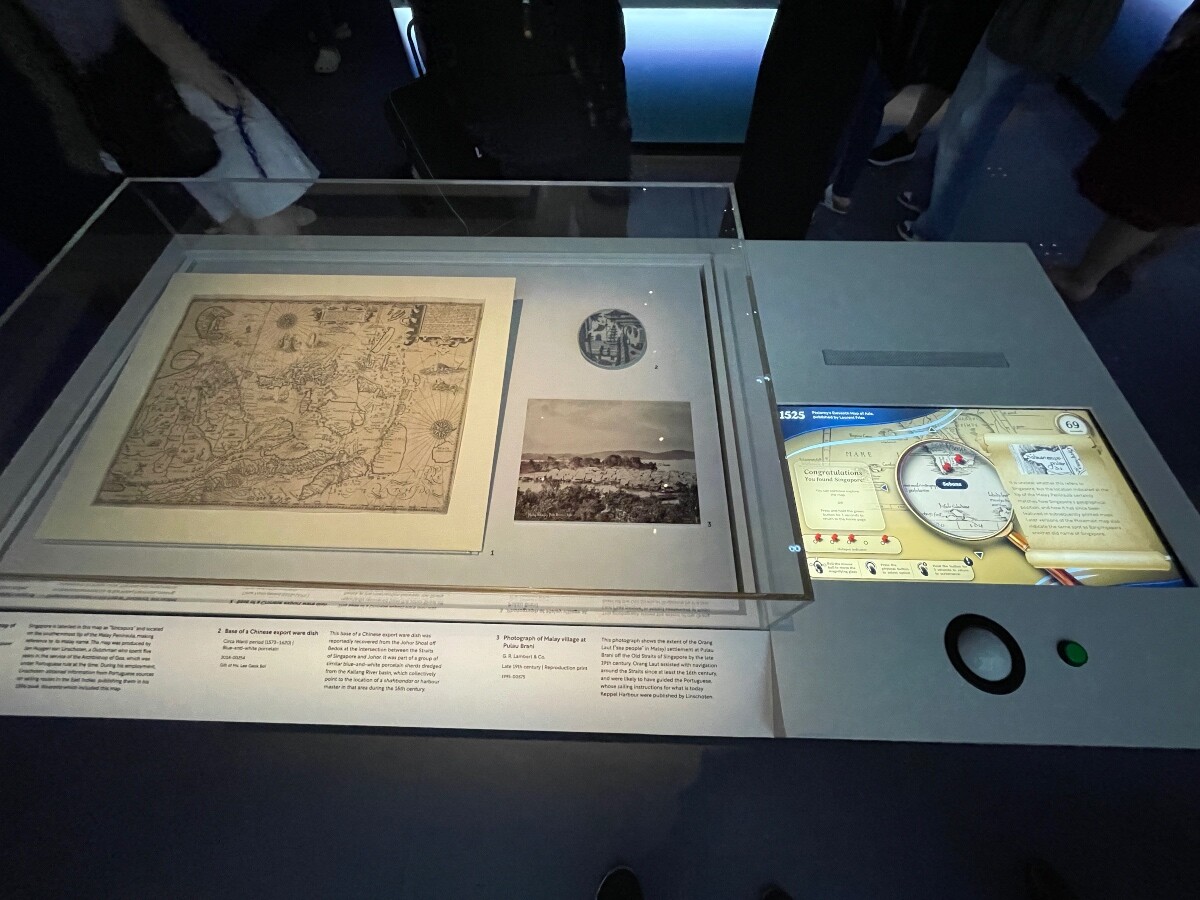

The exhibits that contain these early maps are not merely representations of land, but cryptic parchments bearing the hopes and fears of their creators. Observe the compasses, primitive yet profound instruments that once held the fate of expeditions. But these aren’t just artifacts; they are silent storytellers.

The button and ball controller are for you the explorer to find Temasek!

Every narration etched onto the walls is an invitation—a challenge. It is a carefully crafted prompt designed to ignite your inner sense of adventure. You will instinctively question and piece together fragments of information, while searching for the elusive clues hidden in plain sight. You will embody the early explorer, grappling with the same enigmas, facing the same vastness, and feeling the thrilling pulse of discovery with every step.

With the wrist tag, you can engage in interactive QnA throughout the exhibition. Does Singapore’s early history matter to you? Share your answers in the comment box below.

Chapter Two: The River Road

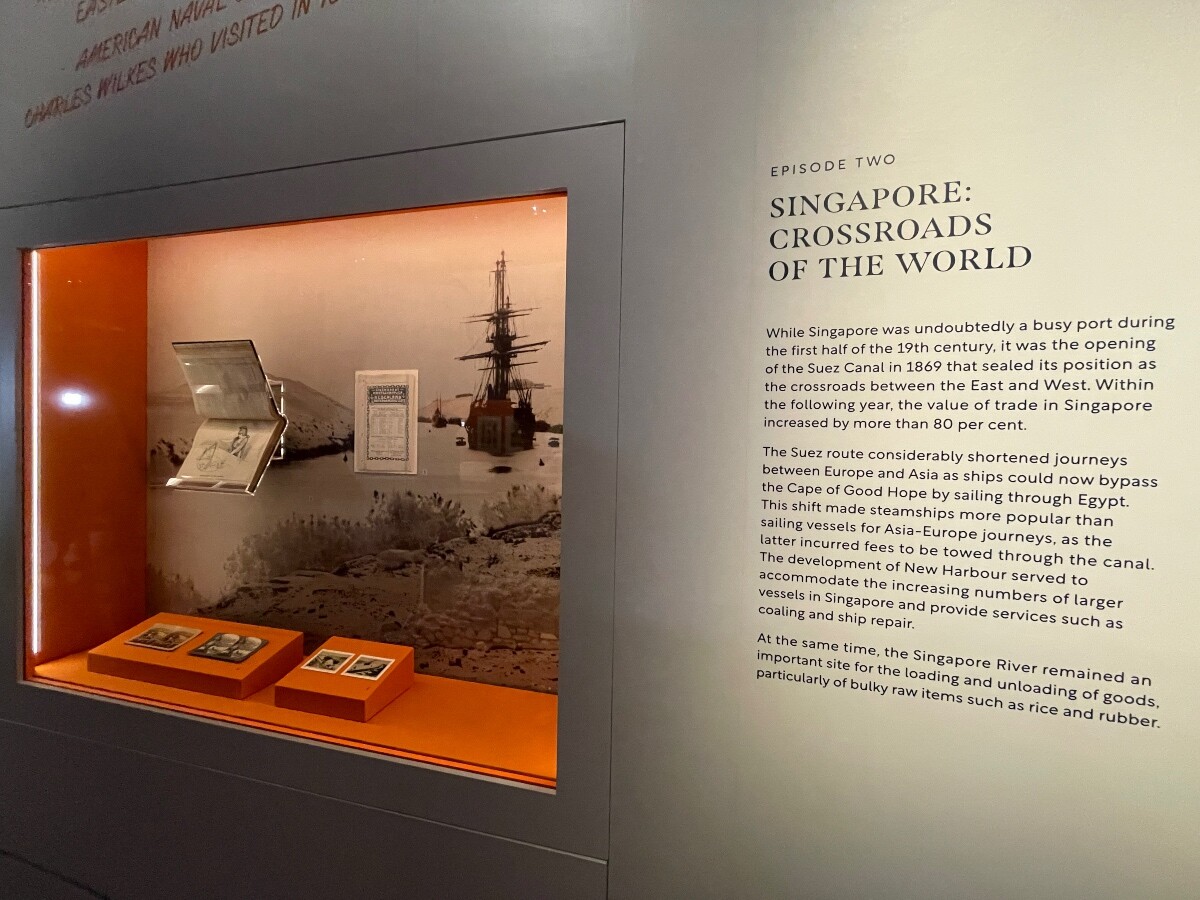

We moved on the Chapter Two, which predominantly highlights Singapore’s geographical location and how it strategically sits along the shipping routes that links trade from the East to the West.

1. Chinese Stoneware Jars (14th Century) (top): Archaeologists found these “small-mouthed bottles,” which people called xiaokouping, near Singapore’s Old Parliament House; these items were common Chinese storage jars. People originally used these jars for liquids like mercury. Later, they reused them for items such as wine or betel lime. The discovery of these jars, along with many other 14th-century trade goods near the Singapore River, indicates significant past settlement and trade in the area.

2. Chinese Celadon Plate (14th Century) (bottom left): A 14th-century Chinese celadon plate found in Singapore, on loan from the Asian Civilisations Museum.

3. Ming Dynasty Chinese Vase (1573-1621) (bottom right): This Ming vase and other similar blue porcelain pieces found in the Kallang estuary suggest that the Kallang River, not the Singapore River, was the main trade route in the 16th-17th centuries. Both the Kallang and Rochor Rivers remained important for trade and shipbuilding during colonial Singapore.

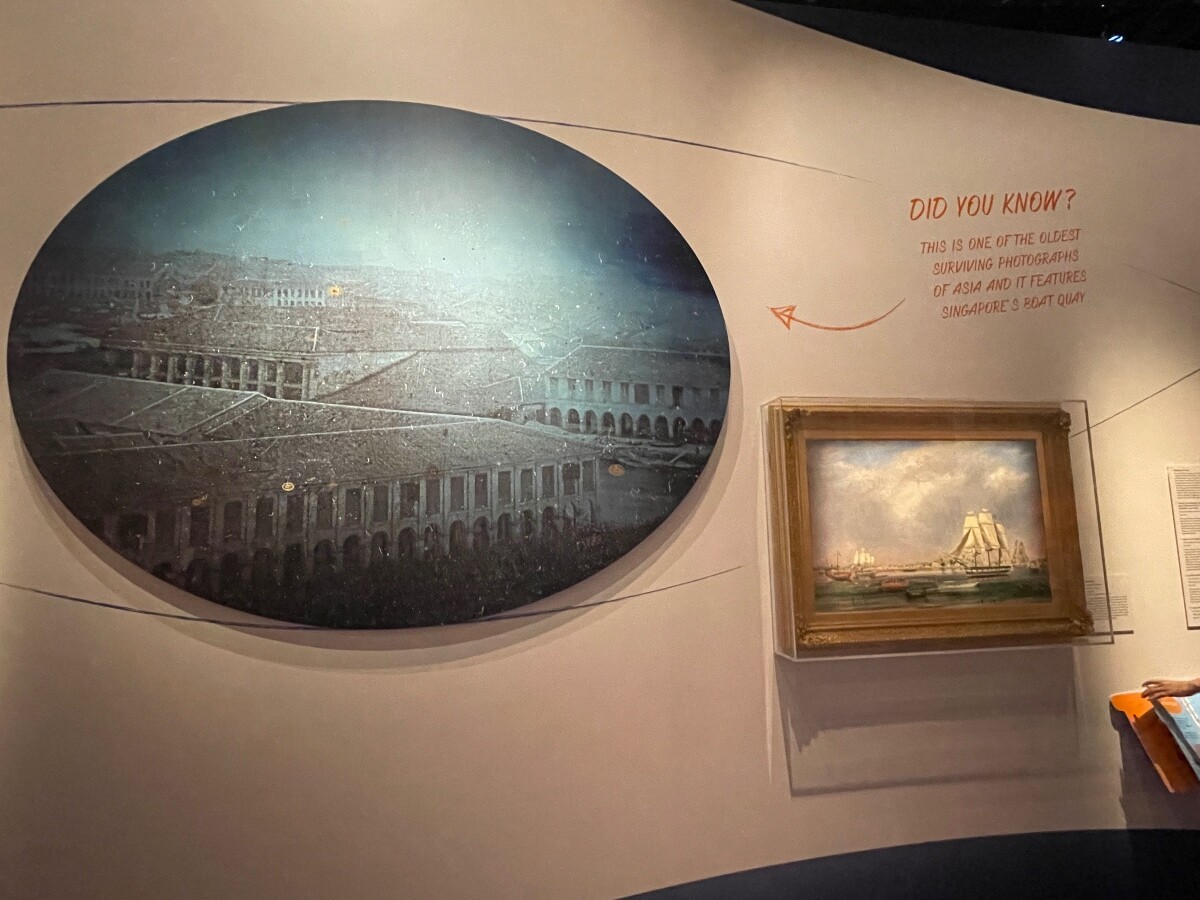

4. Daguerreotype of Boat Quay (1844): This early photograph, taken from Government Hill, shows Singapore’s commercial hub at Boat Quay. Singapore’s success as a trans-shipment center meant new technologies, like daguerreotypy (invented just five years prior), arrived quickly.

5. Print of Singapore River & Presentment Bridge (1830): This print illustrates early Singapore River crossings by boat before the 1823 Presentment Bridge (later Elgin Bridge). It also depicts the diverse population drawn to Singapore for trade and work, seen moving cargo by the river.

6. Italian Postcard of North Boat Quay (Early 20th Century): This postcard features Boat Quay warehouses, including Boustead & Co., and advertises Italian soaps and perfumes.

7. Logbook of the Charles Grant (1834-1835): This logbook details the voyage of the former British East India Company ship Charles Grant. In 1834, it arrived in Singapore from Bombay, then departed for China, and also visited St Helena and England. The log records goods loaded in Singapore, such as pepper, betel nut, and rattan.

A mid-20th century jute cushion (above), worn around the neck, protected coolies’ backs or shoulders from heavy, sharp-edged loads. The 1964 photograph “Working in Unity” by Loke Hong Seng (top right) depicts a labourer using a similar cushion while cooperatively loading rubber bales at Clarke Quay.

The Suez Canal transformed global maritime trade routes in the late 19th century, and Singapore was perfectly positioned to capitalise on this transformation. It was critical to Singapore’s initial “survival” and establishment as a major port, and it remains fundamental to its ongoing “success” as a global trade, logistics, and maritime powerhouse. The Suez Canal is a man-made waterway connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, and it has been profoundly critical to Singapore’s survival and enduring success as a global trade and maritime hub since its opening in 1869.

This 1844 daguerreotype (above) by Alphonse-Eugène-Jules Itier, one of Asia’s earliest surviving photographs, shows Boat Quay and the Singapore River from Government Hill (now Fort Canning Hill). Captured just five years after the daguerreotype process (which creates unique, reversed images) was invented, its presence in Singapore—then a thriving transshipment hub—highlights how quickly new technologies reached the well-connected port.

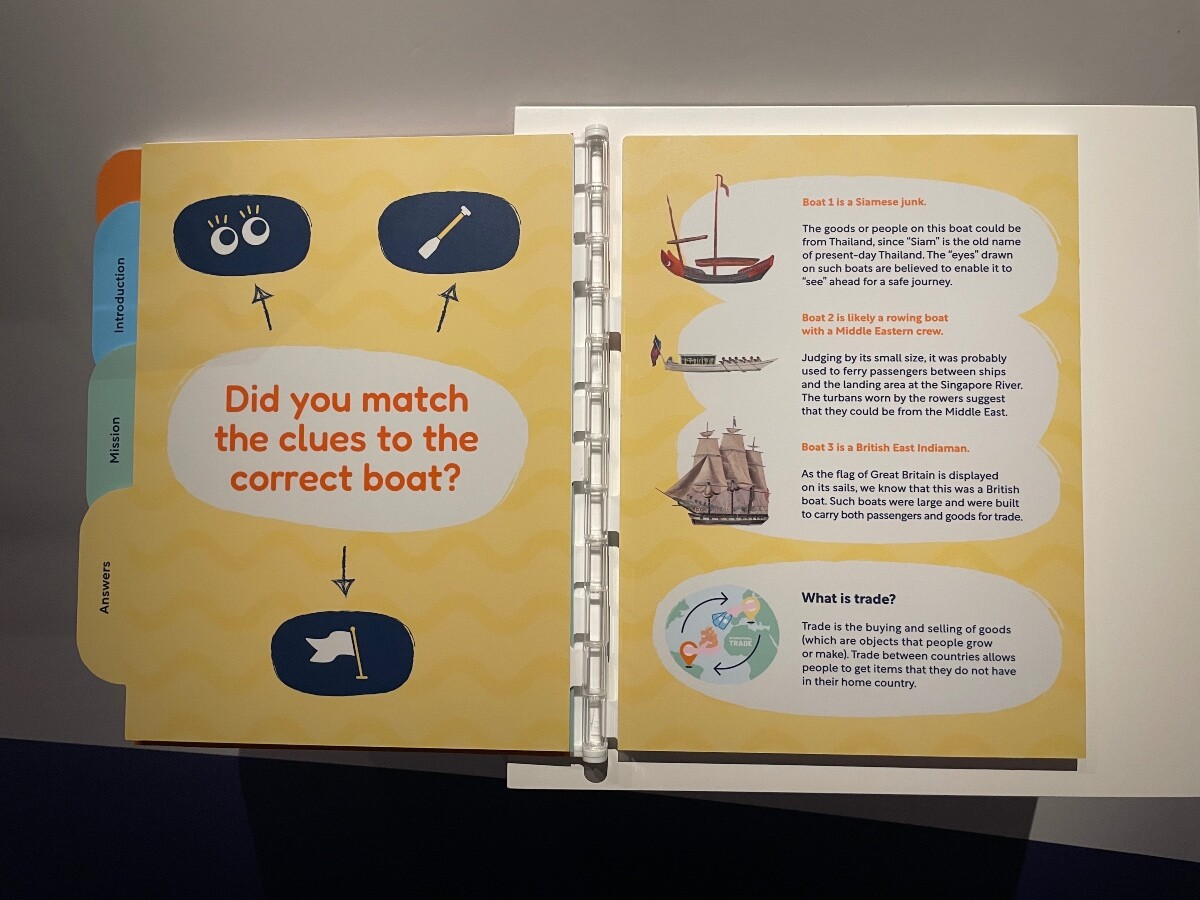

The exhibition has 11 interactive “Waves of Wonder”(above) lift-the-flap captions for children 4+. These easily identifiable, three-page captions (info, task, answers) help kids connect with artefacts and support self-guided tours. They are a collaboration between the National Museum of Singapore and My First Skool educators.

British autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire drew the “Singapore Panorama” (2014, pencil and ink) (above) from memory after a single hour-long helicopter ride. He masterfully depicted the cityscape, including the Singapore River and Marina Bay, using his extraordinary talent to raise autism awareness and charity funds.

For extra fun, try the “Sampan Challenge”: “row” a sampan across the Singapore River, skillfully avoiding other vessels and weathering challenges to deliver your passengers safely. For adults only.

Chapter Three: Expanding Horizons

“Expanding Horizons” complements the main narrative by highlighting Singapore’s innovative land planning to overcome its small size. This section includes artifacts like a letter from Raffles on town planning and a 1976 skyline panorama. Visitors can also use a digital slider map to see Singapore’s coastline changes over centuries, tracing land reclamation efforts back to colonial times.

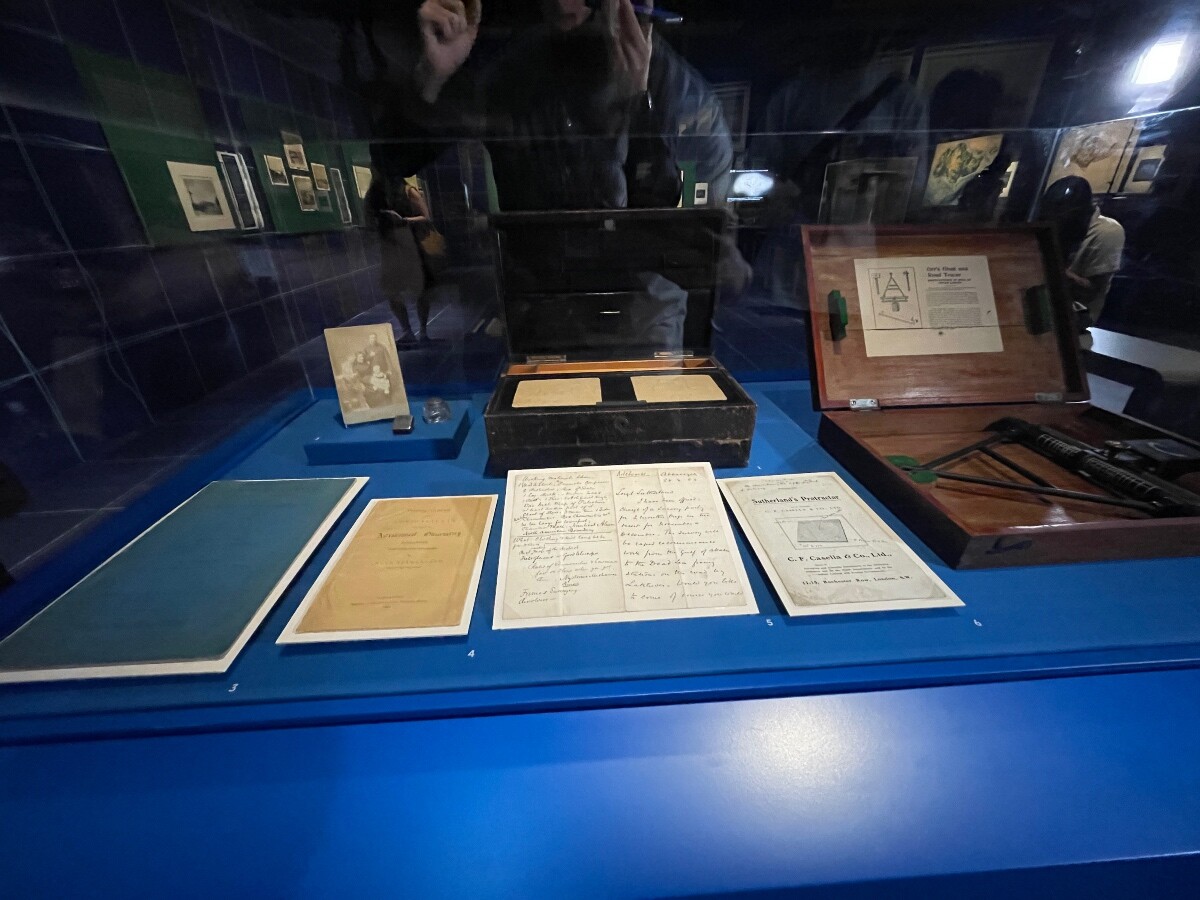

This late 19th-century travel desk (above) belonged to Angus Sutherland, a colonial surveyor in Singapore (1890-1894). He received it in 1886 from Lord Kitchener, with whom he had mapped Cyprus. In Singapore, Sutherland lived on Beach Road and trained surveyors at a new school established to meet the colony’s development needs, teaching theory in the mornings and fieldwork in the afternoons.

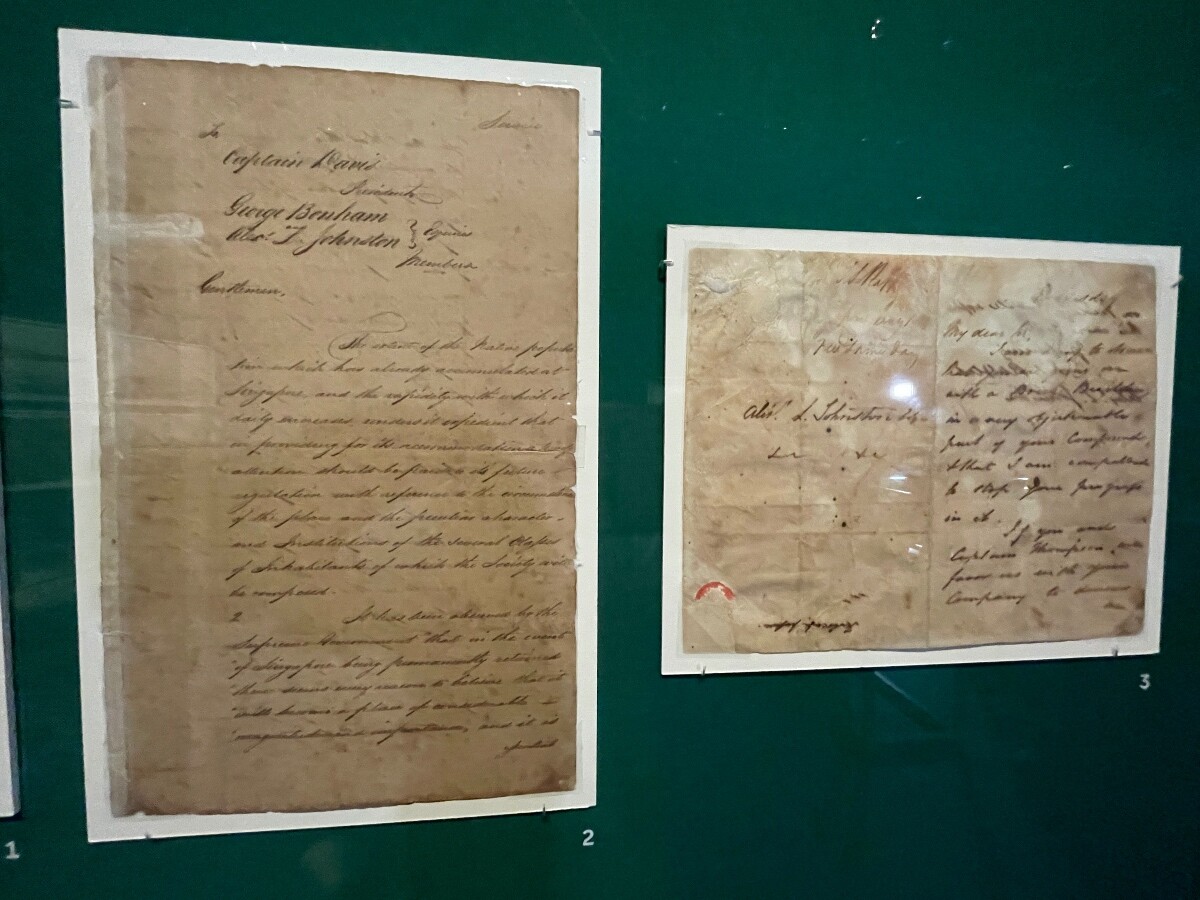

This 1822 letter (above left) from Sir Stamford Raffles to his town planning committee (C.E. Davis, S.G. Bonham, A.L. Johnston) stressed the urgent need to regulate Singapore’s rapidly growing population. To achieve his vision of Singapore as a place of “magnitude and importance,” Raffles’ plan included allocating land for government and commerce, and controversially, creating ethnic enclaves.

In this May 1823 letter (above right), Raffles reprimanded Alexander Laurie Johnston—an early settler, founder of A. L. Johnston & Co., and President of the town planning committee—for building a large godown without permission, viewing it as undermining his town plan. It’s unclear if Johnston received the letter or stopped construction.

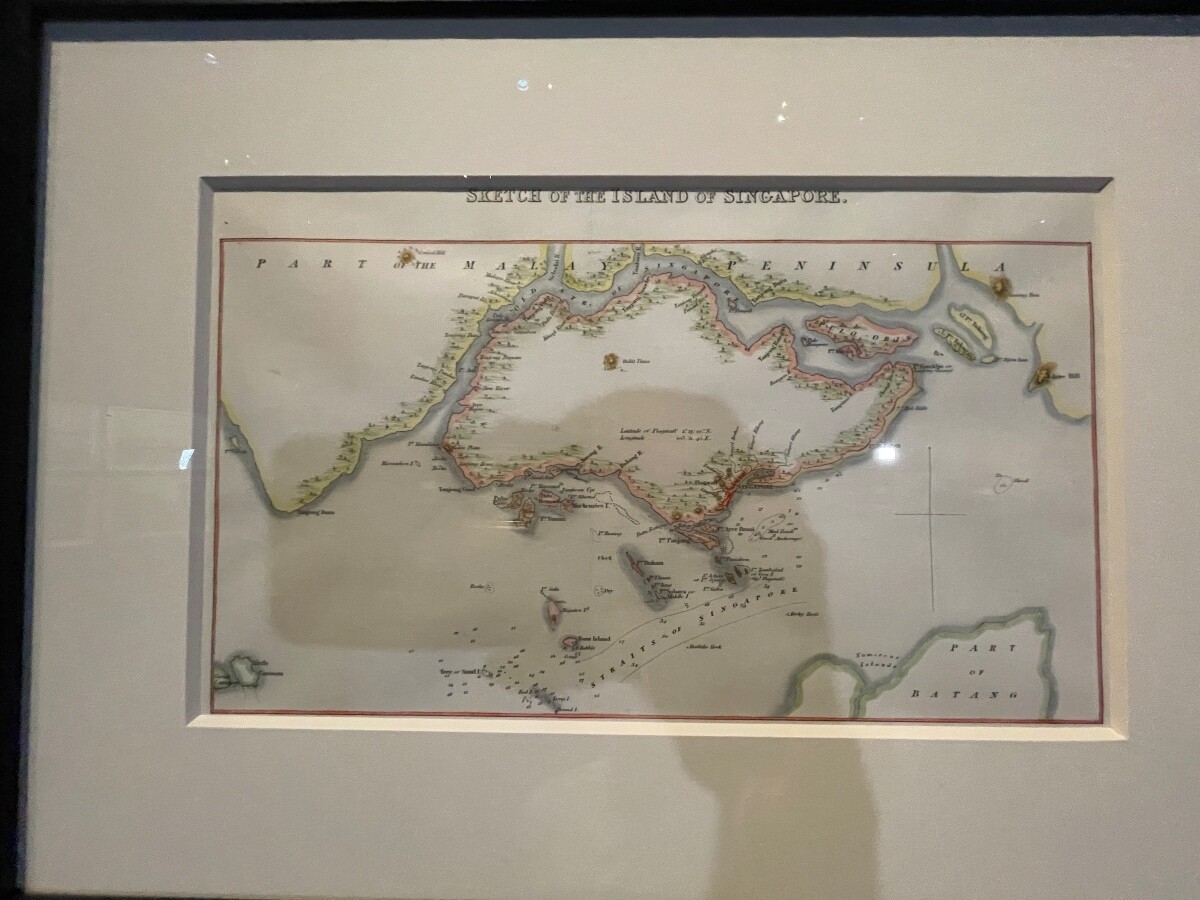

This 1830 hand-coloured engraved sketch (above) of Singapore Island, featured in Lady Sophia Raffles’ memoir, closely follows Captain Franklin’s 1822 plan but adds more detail on coastal vegetation, nearby hills, and an expanded view of the Straits of Singapore. (Gift of Capitaland)

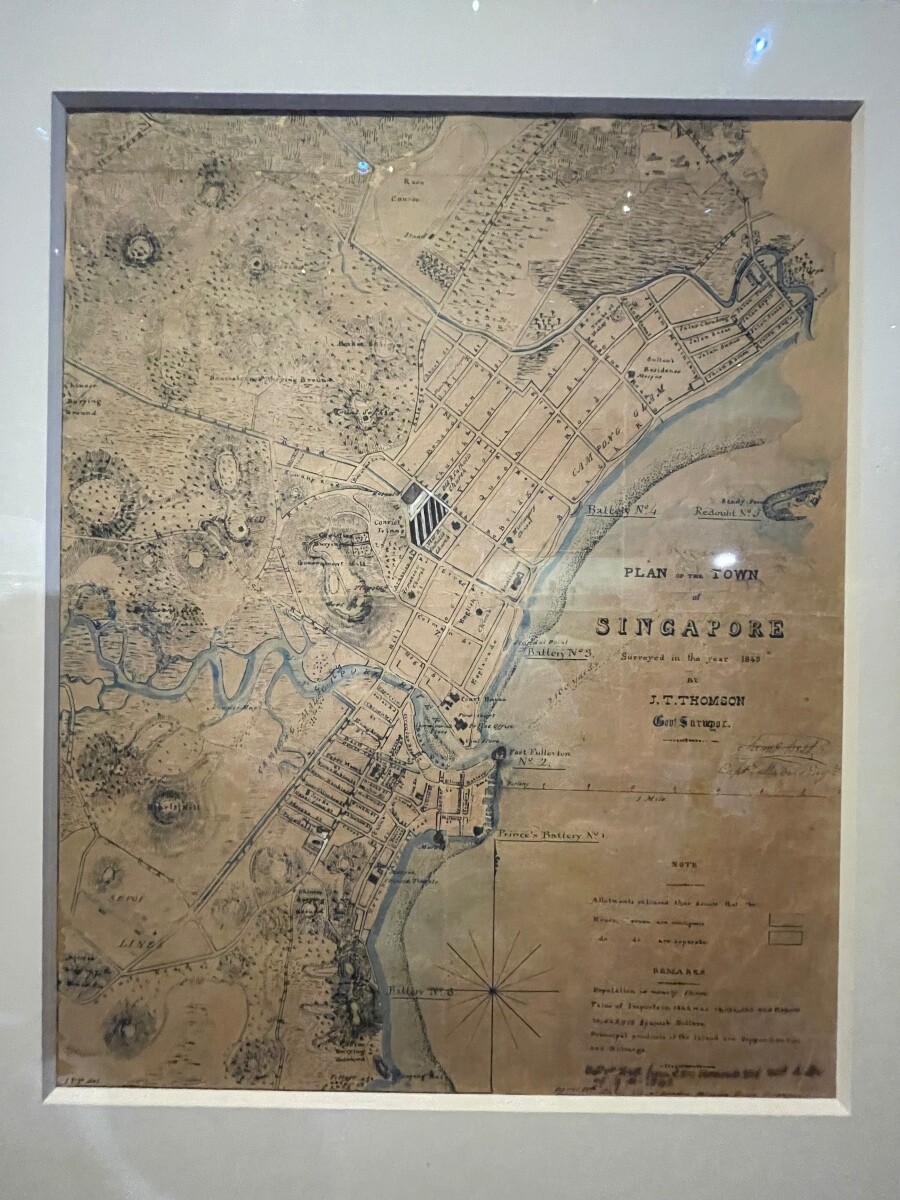

J. T. Thomson’s 1843 hand-coloured lithograph (above) is Singapore’s earliest known printed map. Based on a government survey, it shows the town’s inland expansion, road construction, and hill details when the population reached 50,000. The map, owned by Captain James Best who proposed military fortifications, reflects this period of development.

Lai Kui Fang’s 1977 oil painting (above), “Skyline of Singapore in 1976” (on loan from Istana Art Collection), vibrantly details the city centre’s increased density and height within Singapore’s first decade of independence. It portrays ongoing development, including the early reclamation of Marina Bay for Marina Centre.

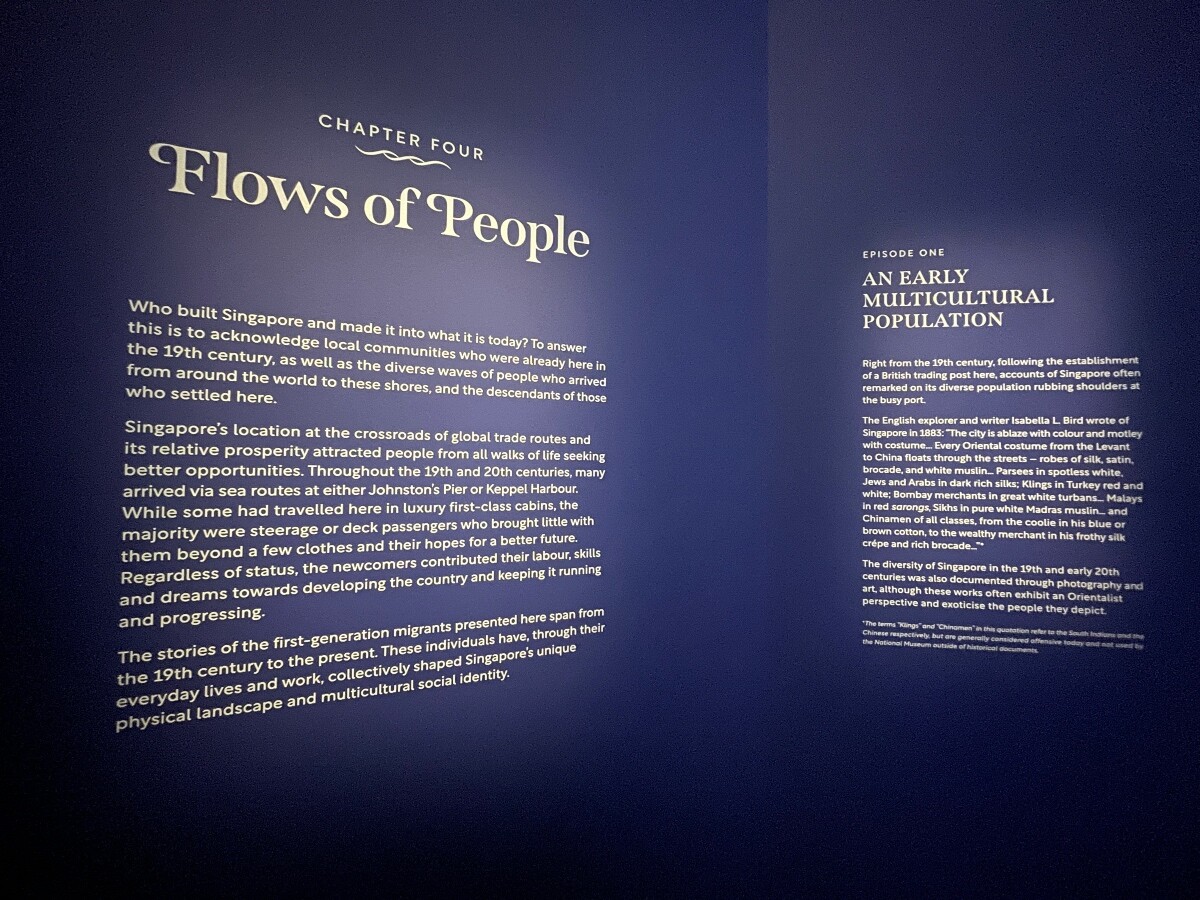

Chapter Four: Flows of People

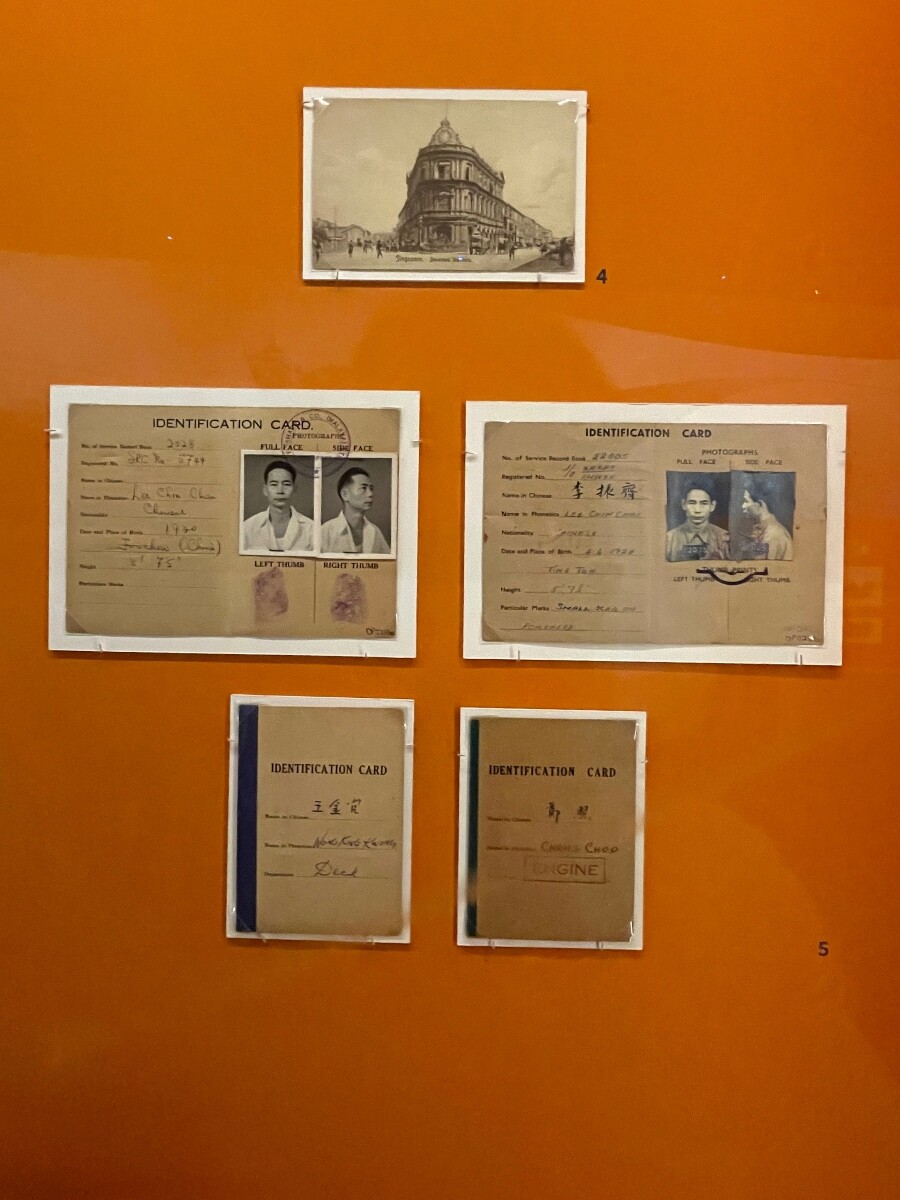

Chapter Four honors individuals, from early settlers to today’s workers, who shaped Singapore’s multicultural identity. It explores their diverse experiences and roles in nation-building through personal stories, photos, and mementos. The chapter also connects past and present occupations, showing how essential roles continue to evolve in Singapore’s history.

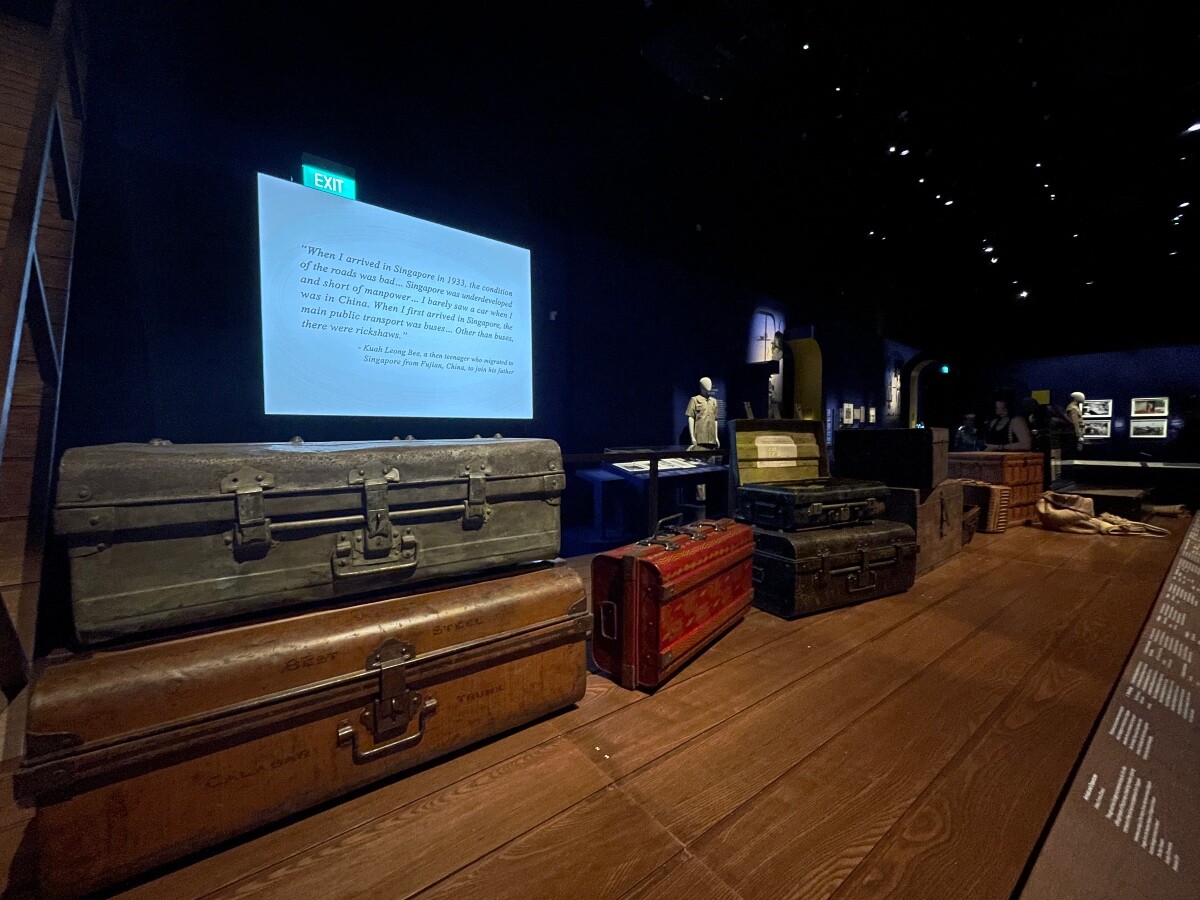

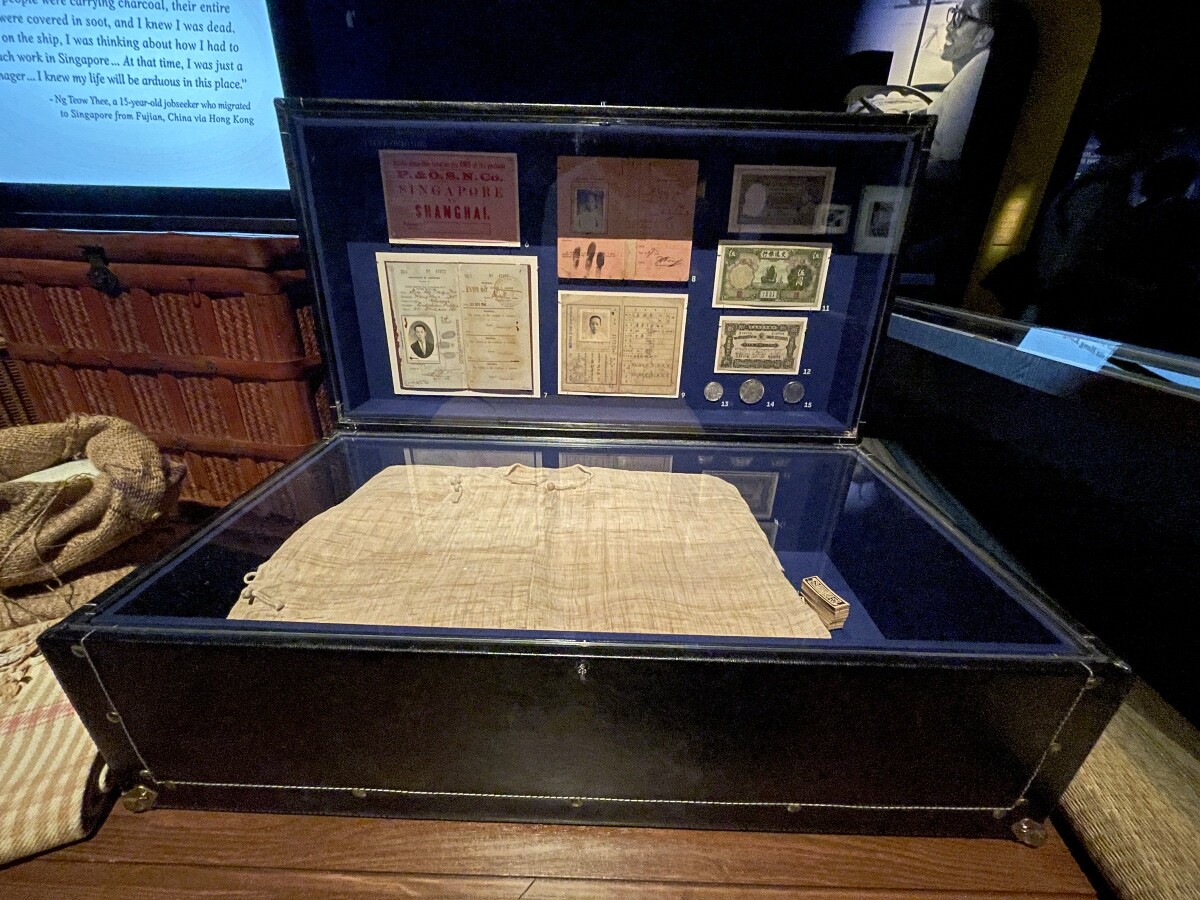

Immigrants brought these steel and rattan trunks to Singapore as their sole keepsakes from home, often retaining them for decades to store personal items.

During this era, manufacturers robustly built travel trunks, typically of wood or steel. They equipped these trunks with strong locks, often waterproofed them, and added external protection like bolts for stacking (as seen on the Jones Brothers & Co trunk) to help the trunks withstand rough ship, rail, and road journeys. In the late 19th century, designers also created lighter, more fragile rattan suitcases, which they intended for hand-carrying and often included an inner pocket for shirts; these suitcases also emerged during this period.

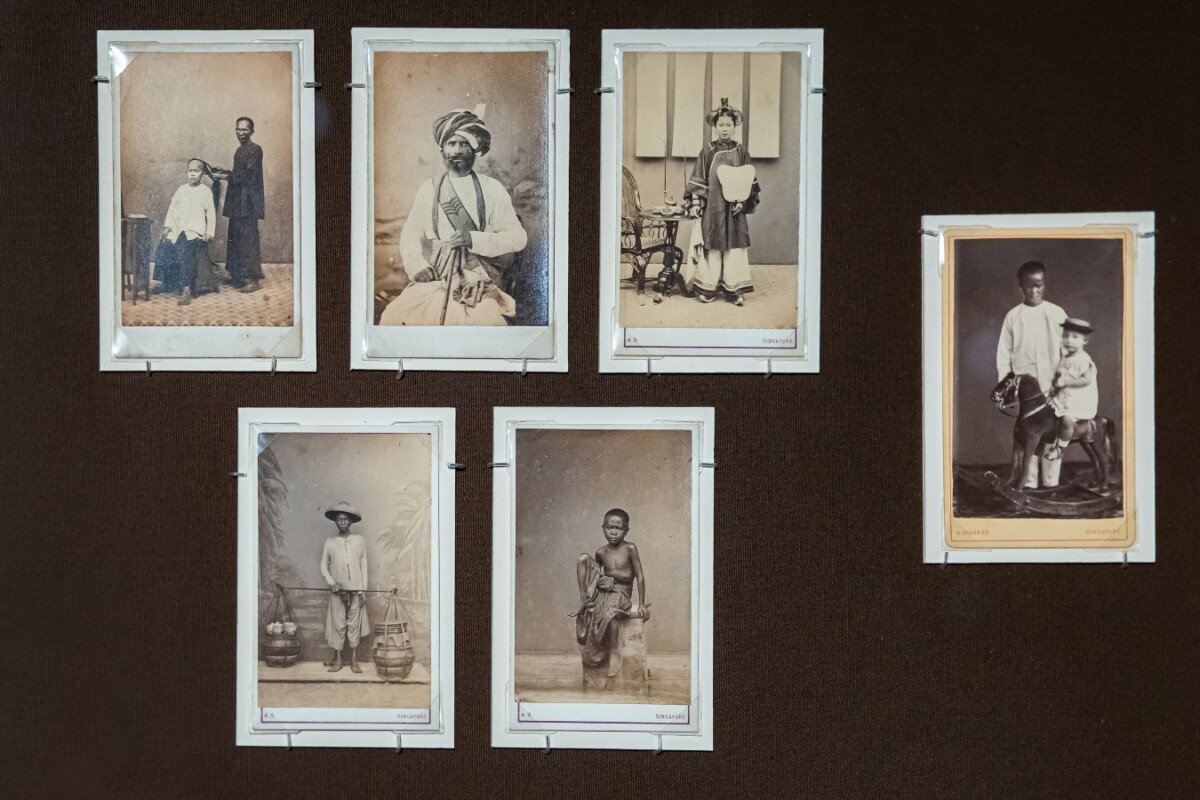

In the 1860s, August Sachtler produced carte de visite portraits (above) that aimed to capture “types” of people in Singapore. These photographs, used as visiting cards or souvenirs, offer a view of Singapore’s diversity through an European lens. Sachtler’s firm also published “Views and Types of Singapore,” an early photo album.

This diorama vividly portrays a “coolie keng” from 1900s Chinatown, revealing the harsh living conditions of early laborers. These densely packed rooms featured multi-tiered wooden bunks. Each cubicle rented for $1.50 to $4.50 monthly, often shared by workers on alternating shifts. The scene captures coolies at rest, eating, or consuming opium. While opium provided temporary escape from their physical and mental suffering, its addictive nature frequently led to them losing their jobs and homes.

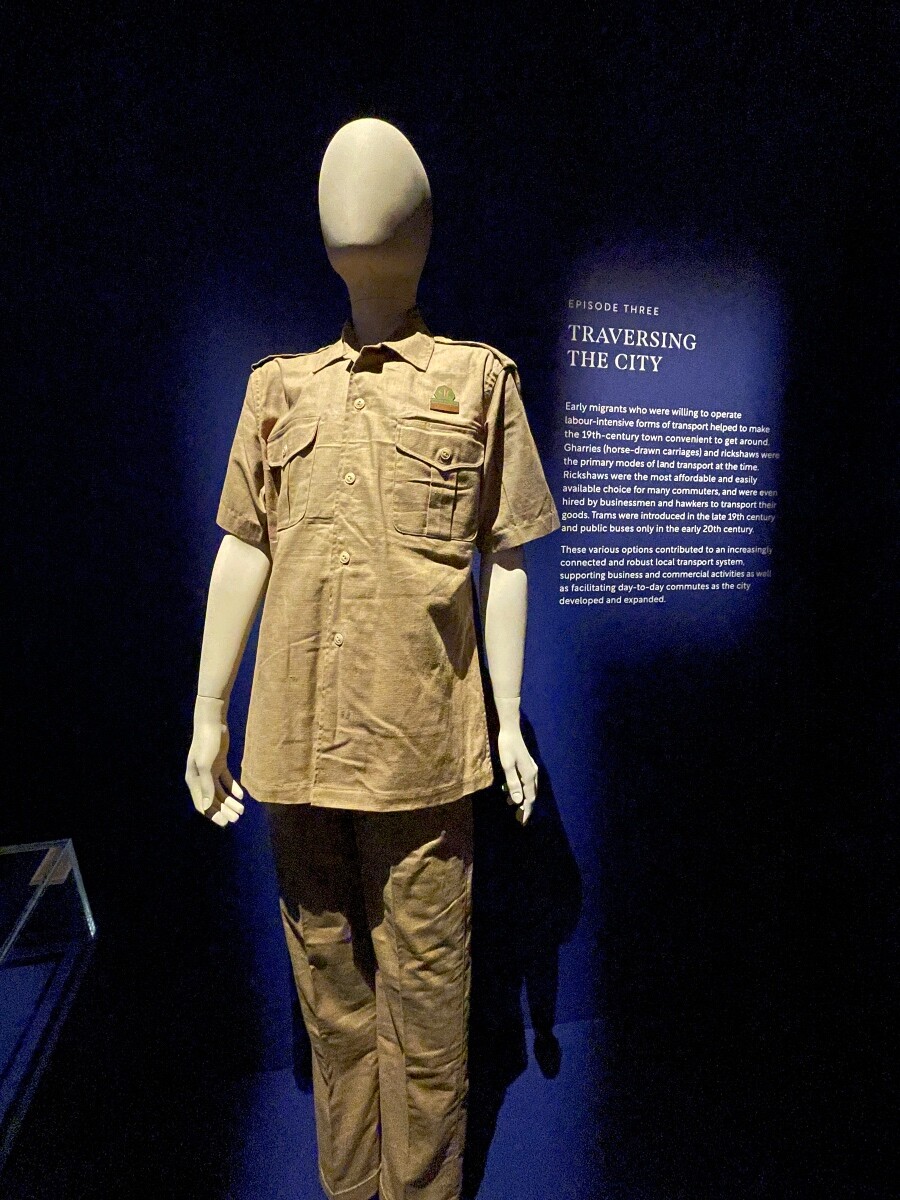

This mid-20th century fabric bus driver’s uniform and a 1930-1945 metal bus driver’s badge (above) are from the Singapore Traction Company (STC).

Historically, Singapore’s earliest buses were small, unlicensed seven-seater “mosquito buses,” mostly operated by Fujian immigrants. The British-owned Singapore Traction Company, established in 1925, came to dominate city centre trolley and motor bus operations before World War II, pushing mosquito buses to the outskirts. However, the STC suffered heavy losses during the Japanese Occupation and struggled by the 1960s. It eventually closed in 1971, with other companies taking over its fleet.

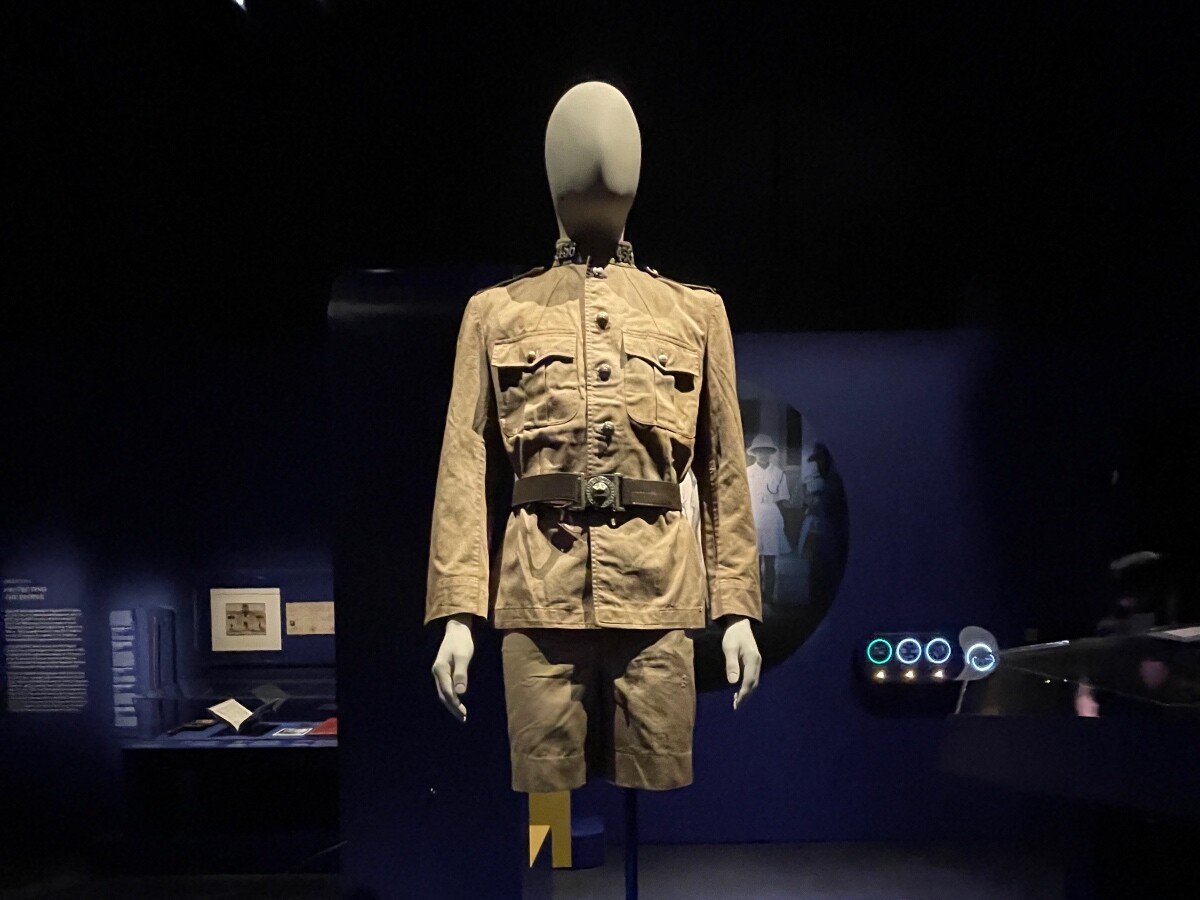

This early to mid-20th century fabric police constable’s uniform (above) exemplifies officer attire in Singapore at the time. Until the 1960s, patrolling constables wore khaki uniforms featuring shorts, a practical adaptation for the tropical climate. The elite Sikh Contingent, established in the 1880s, enforced strict physical standards for its recruits, requiring a minimum height of 175 centimetres and a chest measurement of at least 96.5 centimetres, reflecting the demanding nature of their duties.

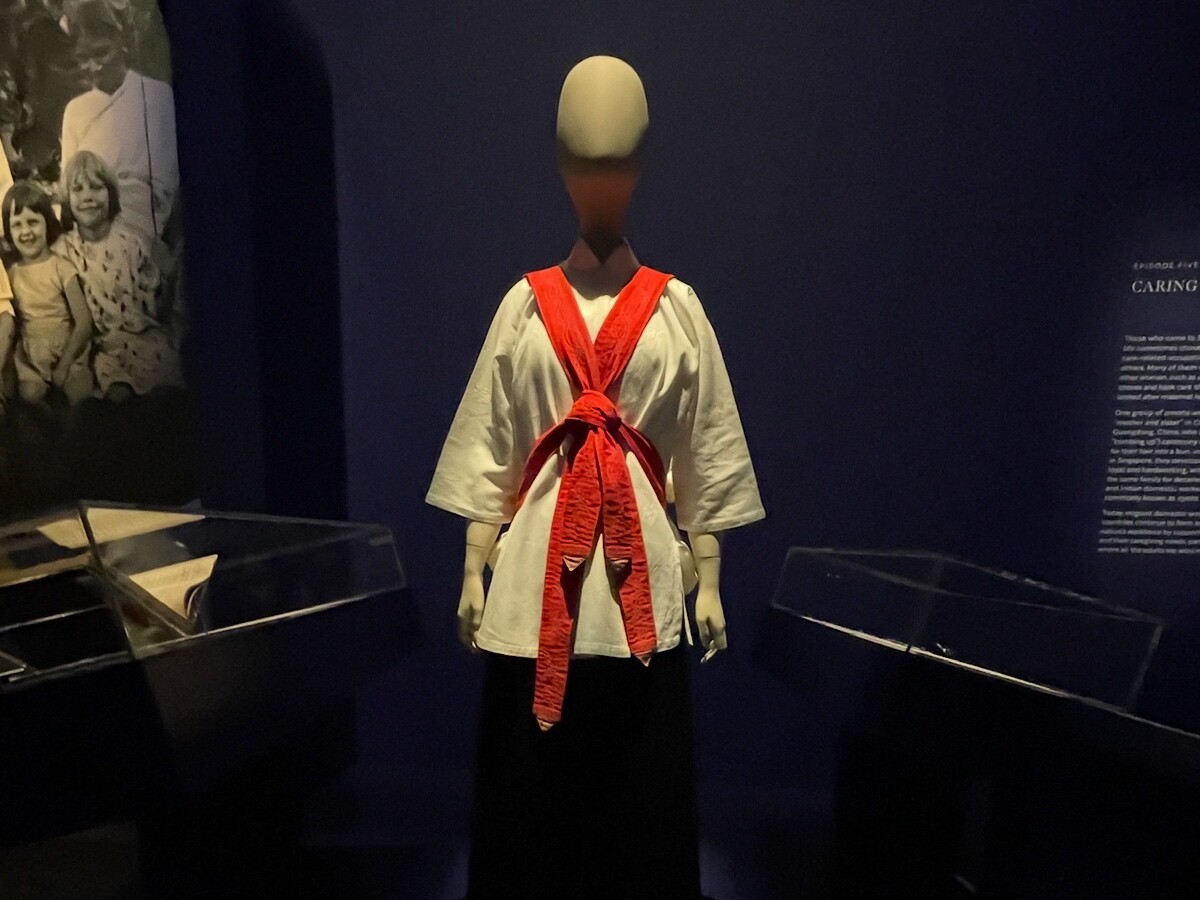

This mid-20th century cotton and silk samfoo (above) belonged to Majie Leong Kun Toh. Most female domestic workers (amahs and majies) in early to mid-20th century Singapore were from Guangdong, China. Back then, poverty is widespread with a declining silk industry. They were recognisable by their simple black-and-white samfoos. More on Majie Leong’s story is available near her displayed comb and hair clip. (Gift of Dr Mark Lu)

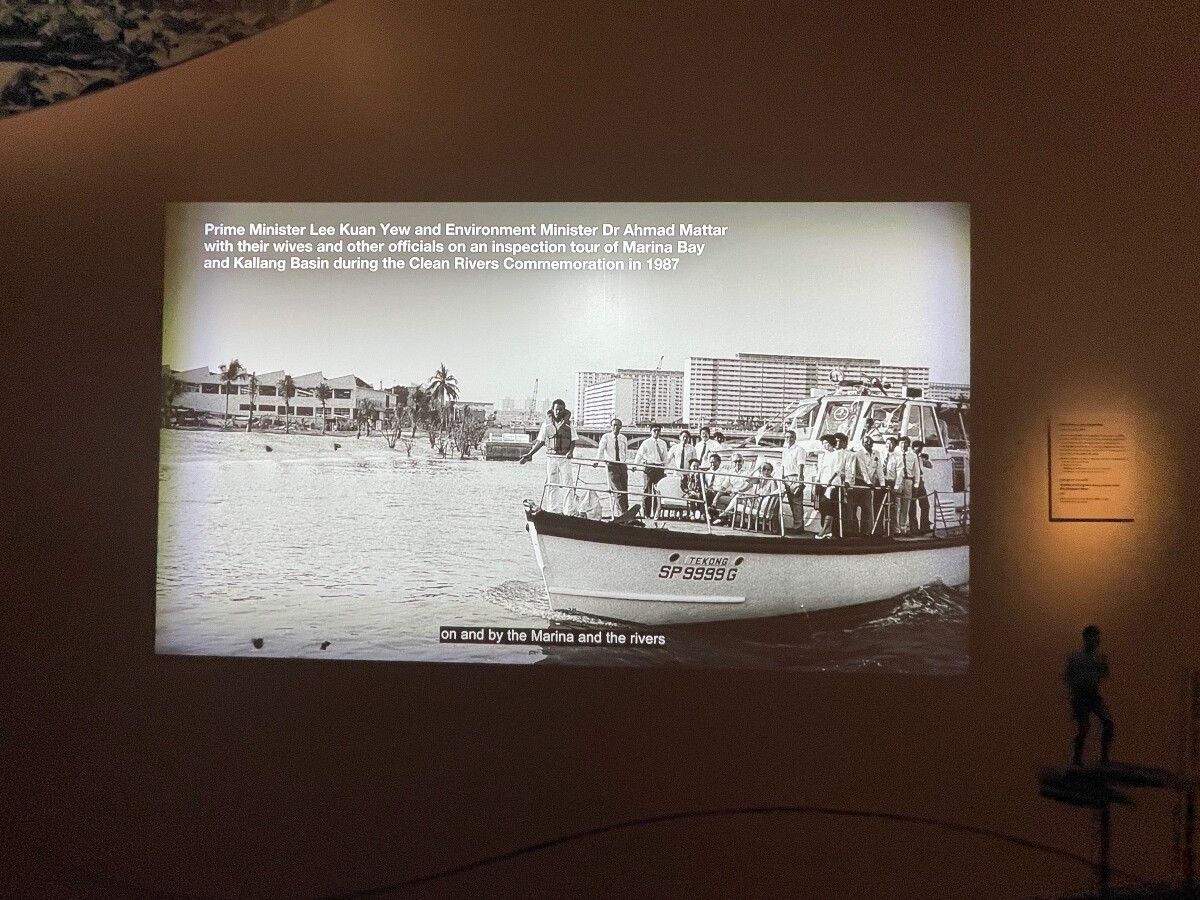

In 1987, Singapore’s Clean Rivers Commemoration celebrated a decade-long effort to clean its polluted Singapore River and Kallang Basin. Previously, waste from industries, hawkers, and squatters choked these rivers, turning them into open sewers posing health risks. The government initiated the ambitious clean-up in 1977, resettling people, diverting waste, and dredging the polluted rivers. More than cleaner water, this 1987 event symbolised national triumph, environmental commitment, and improved quality of life for Singaporeans. It marked a visible turning point in how Singapore viewed and managed its urban environment.

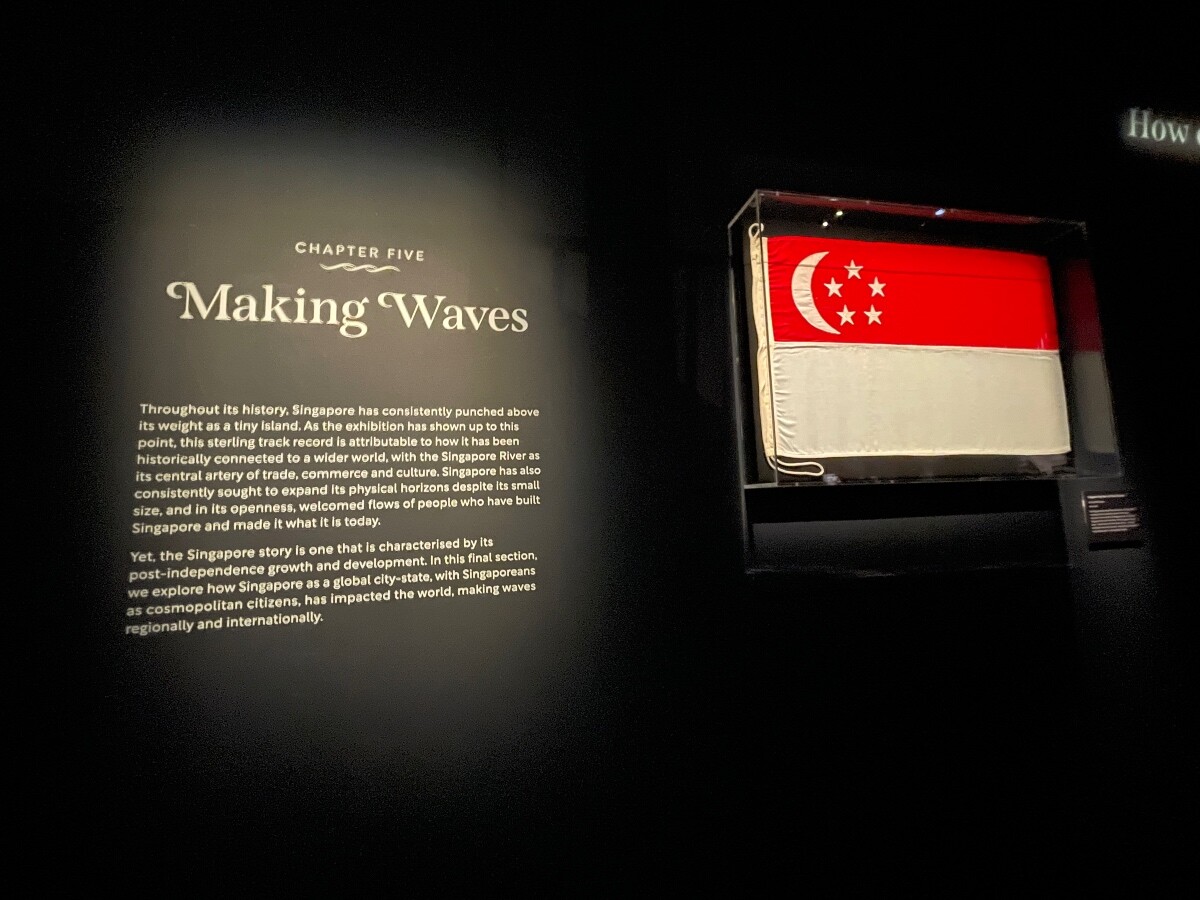

Chapter Five: Making Waves

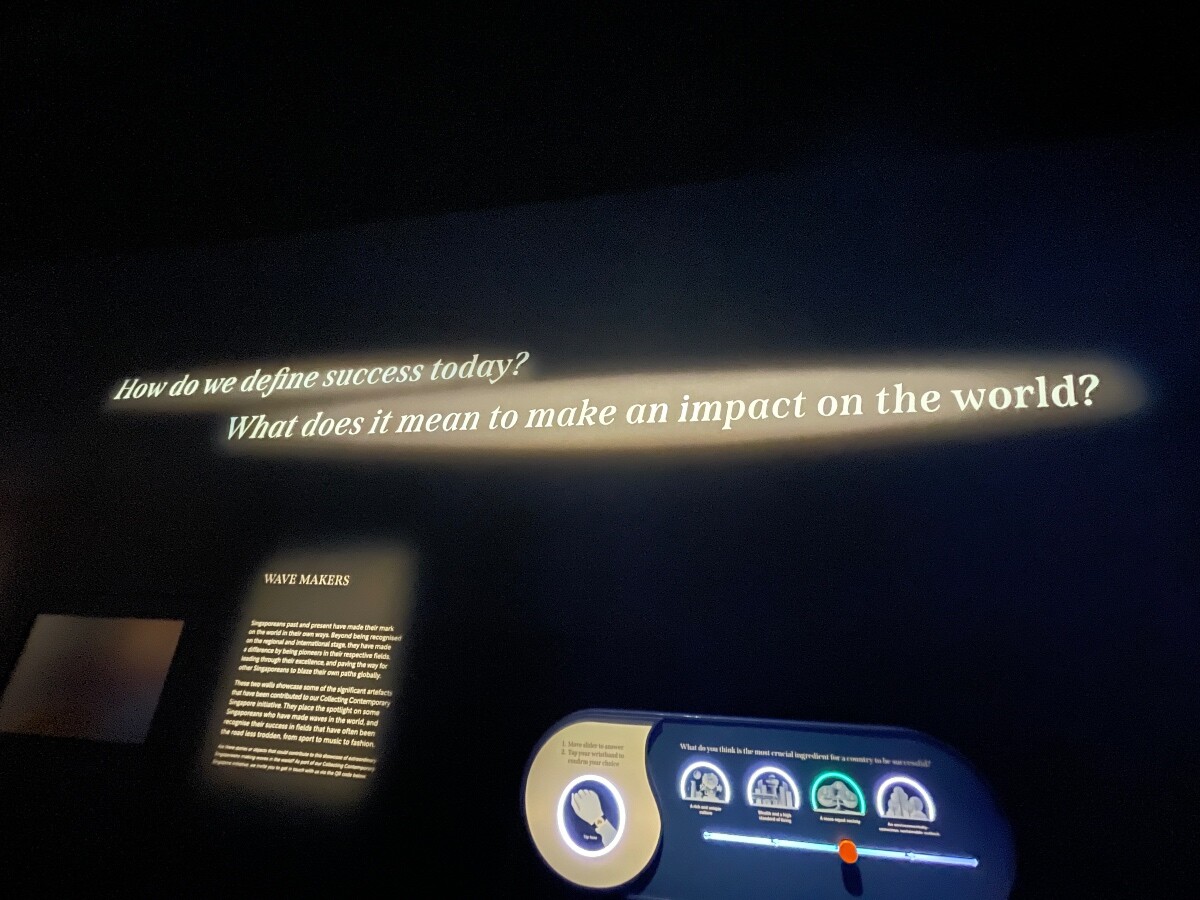

This concluding chapter, titled “Making Waves,” celebrates Singaporeans and local entities that have achieved significant global recognition. It highlights their impactful contributions across diverse fields like diplomacy, humanitarian endeavors, and technological innovation. The section also showcases Singapore’s role in developing key international hubs since its independence in 1965.

The exhibition shares inspiring stories of these trailblazers who have profoundly shaped Singapore’s global identity. It proudly spotlights unique local expressions that have gained worldwide acceptance, such as the inclusion of “Singlish” in the esteemed Oxford Dictionary. Furthermore, the chapter recognises local cuisine for its widespread international acclaim, reflecting Singapore’s rich culinary heritage. Visitors can also engage with an interactive quiz to test their knowledge of Singlish phrases and their meanings.

Singapore’s Global Achievements: Scaling Heights

This 1998 rayon Singapore flag (above right) holds significant historical value, as it was proudly planted atop Mount Everest. The flag was placed there by Singaporean climbers Edwin Siew and Khoo Swee Chiow, signifying their monumental achievement. Their successful ascent marked the first time a Singaporean team conquered the world’s tallest mountain, reaching the 8,848-meter summit. This momentous event, occurring at 8:30 am Singapore time, powerfully showcased Singapore’s ambitious determination to scale global heights.

Singapore’s Global Achievements: Humanitarian Efforts

Dr. Ang Seng Bin wore this particular 2004 armband (above), featuring the Singapore flag (41cm x 21cm), during a critical humanitarian mission. He participated in Operation Flying Eagle, a major relief effort following the devastating tsunami. Dr. Ang, a family physician at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, was holidaying in Penang when the December 26, 2004 tsunami struck nearby. Deeply moved by the crisis, he immediately volunteered his medical expertise with Mercy Relief. He was then deployed to Banda Aceh as part of a medical team. The team diligently treated over 300 patients daily within a makeshift classroom. (Gift of Dr. Ang Seng Bin.)

Singapore’s Global Achievements: Innovation in Crisis

The Infrared Fever Screening System (IFSS)(above) was a groundbreaking invention from 2003, developed by Singapore’s Defence Science and Technology Agency (DSTA). This innovative system was specifically designed to combat the urgent SARS crisis by enabling rapid, mass fever detection. It was quickly co-developed with ST Electronics, utilising a military-grade camera, and a functional prototype was remarkably ready within just 36 hours. The IFSS was swiftly deployed at Changi Airport within a week, significantly reducing the manpower needed for temperature checks. This efficiency greatly accelerated the isolation of potential SARS cases, helping to contain the outbreak. This world-first system garnered international recognition, notably by Time Magazine as a top invention of 2003. Its success paved the way for the widespread mass screening technologies we see today. This artifact is on loan from DSTA.

Singapore’s Global Achievements: Sporting Triumphs

These autographed Nike Air Zoom Maxfly shoes (above), crafted in 2023 from synthetic materials, foam, carbon fiber, and rubber, were a generous gift from Singaporean athlete Shanti Pereira. Wearing this exact pair, Pereira achieved an historic victory in the women’s 200-meter final. This momentous win occurred at the 19th Asian Games in Hangzhou on October 2, 2023, securing Singapore’s first athletics gold medal since 1974. This remarkable accomplishment followed just five weeks after she made history as the first Singaporean to reach the semi-finals of the Athletics World Championships.

These autographed Mizuno GX Sonic III swimming shorts (above), made of nylon and Lycra in 2016, were famously worn by Joseph Schooling. He wore them when he became Singapore’s first-ever Olympic gold medallist. Competing in the men’s 100-meter butterfly final at the Rio de Janeiro Summer Olympics on August 12, 2016, Schooling achieved a truly historic victory. His winning time of 50.39 seconds not only secured gold but also established new national, Asian, and Olympic records. (Gift of Joseph Schooling)

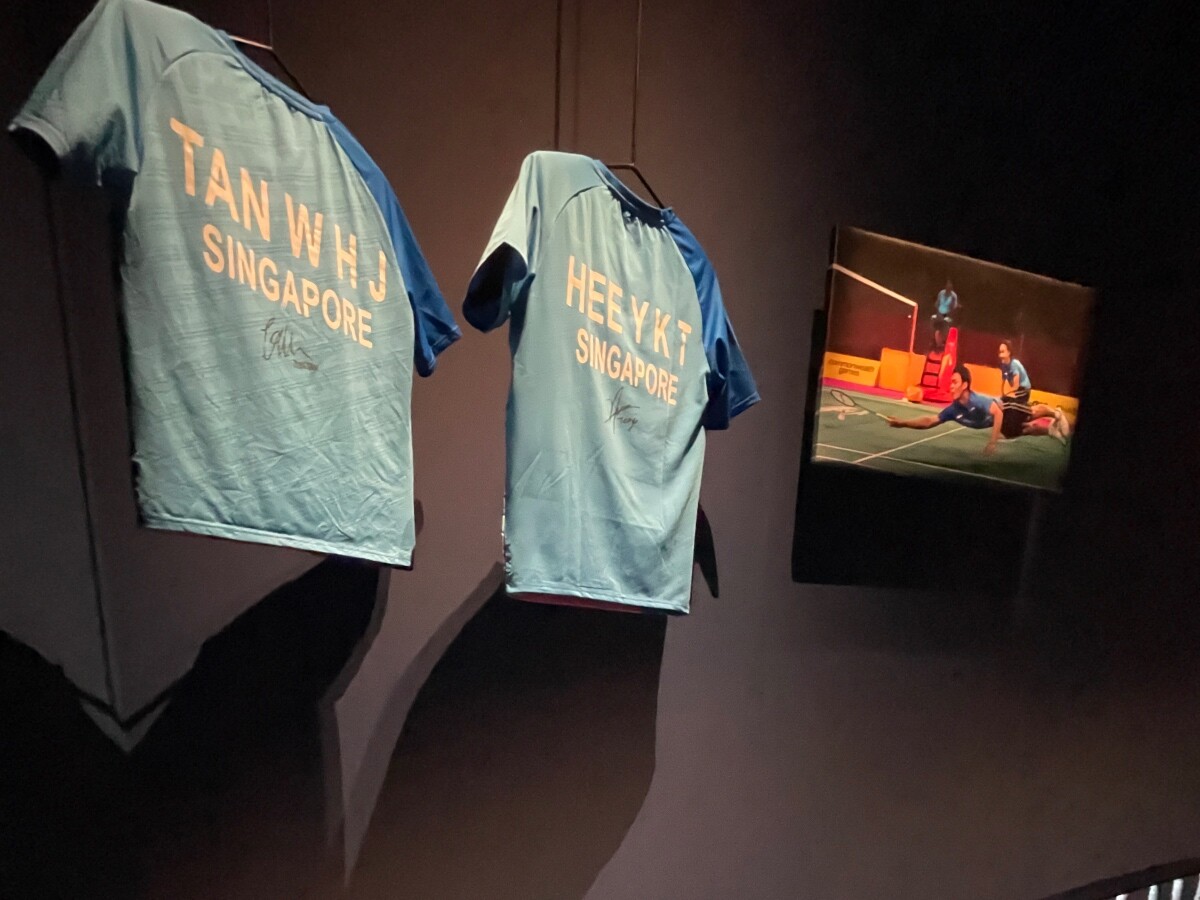

Terry Hee and Jessica Tan wore these 2022 synthetic Li Ning jerseys during their triumphant Commonwealth Games performance. They became the first Singaporeans to secure a gold medal in badminton mixed doubles. In Birmingham on August 8, 2022, the husband-and-wife team celebrated a hard-fought victory. They triumphed over England’s Marcus Ellis and Lauren Smith in the final, following a crucial win against Malaysia’s top seeds, Tan Kian Meng and Lai Pei Jing, in the semi-finals. (Gift of Terry Hee and Jessica Tan)

This impressive gold medal, crafted from metal and nylon, was won by Remy Ong. He earned it at the 2006 WTBA World Tenpin Bowling Championships in Busan, where he also secured the prestigious all-events title. Since this significant 2006 victory, Ong has consistently held the record for the men’s singles six-game series at these championships. As a leading Singaporean bowler, he also notably captained the men’s team at the 2002 Asian Games in Busan. In that competition, he impressively won three gold medals across the singles, trios, and masters categories. (Gift of Remy Ong)

Singapore’s Global Achievements: Cultural Impact

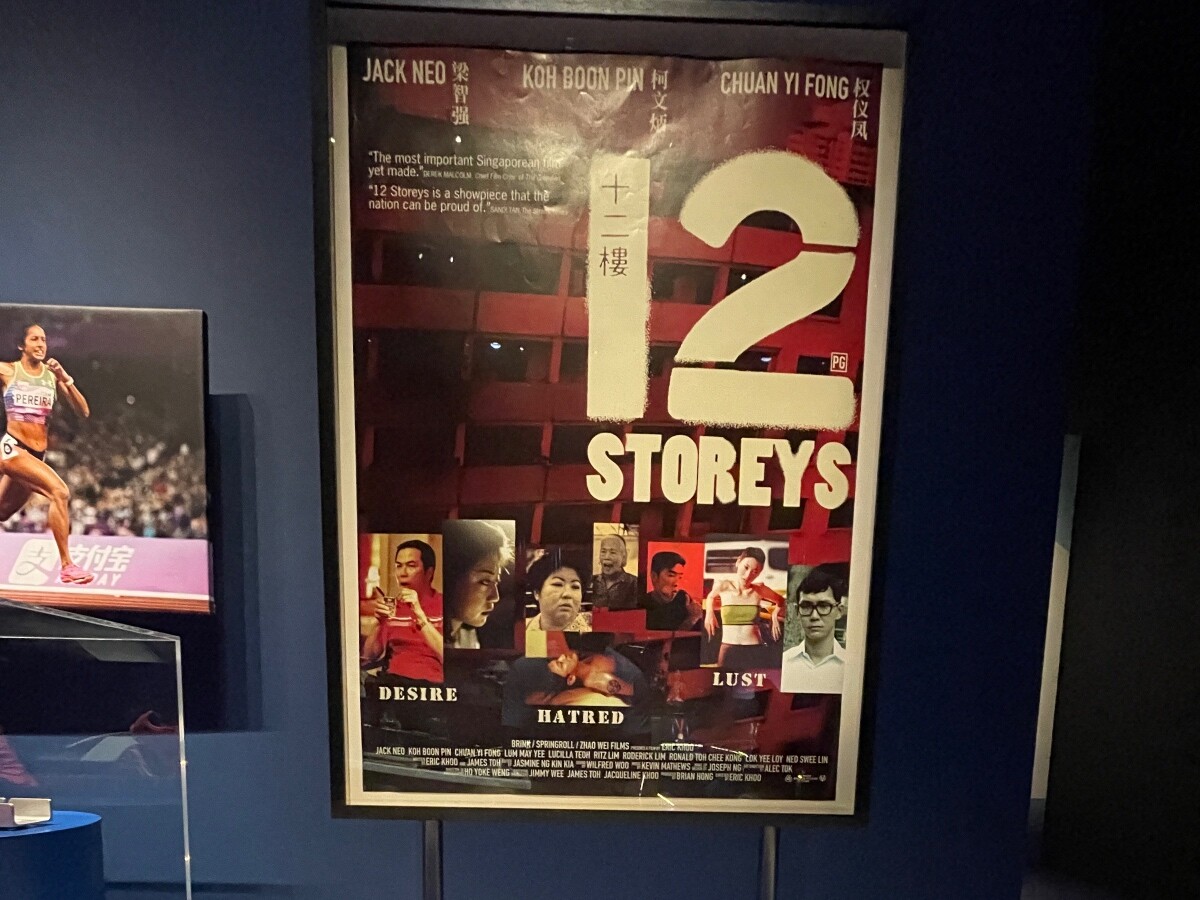

The 1997 Cannes Film Festival screening of Eric Khoo’s “12 Storeys” marked a pivotal moment for Singaporean cinema. It was the first time a film from Singapore achieved this prestigious international recognition. Khoo’s groundbreaking work significantly invigorated the local independent film scene, especially from the 1990s onward. His success created a vital pathway for future generations of filmmakers to achieve similar international acclaim. This led to subsequent successes like Boo Junfeng’s “Sandcastle,” which premiered at Critics’ Week at Cannes in 2010. Furthermore, it paved the way for Anthony Chen’s “Ilo Ilo,” which earned Singapore its first Caméra d’Or at Cannes in 2013, solidifying Singapore’s presence in global cinema.

Once again, the team at National Museum of Singapore has made this a not to be missed event this June holidays. You can spend easily 2-3 hours to truly appreciate the work put into this production. Thanks to Daniel and his team!